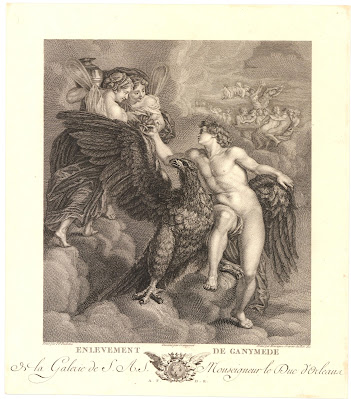

Some years back I published this picture on The MALMESBURY NOW AND THEN FACEBOOK PAGE

Some years after that, a lady named Kat Thompson contacted me, saying Frank was her father but she hardly knew him. She asked if I could write down a recollection for her.

That was in April 2017, and I didn't see her message until the following October, by which time I was severely exhausted by my work and we were desperately home-seeking.

At that time my hours were consumed with an exhausting driving job, and we were about to retire ( I was 68 years old ) and move from London to Tenby, so there was a delay of a whole year before I could settle down and respond. Inexcusable !

So I only wrote it and sent it to Kat a whole year later in October 2018. Kat had contacted me via Facebook Messenger, so I replied via that platform and attached my text as a Word File.

There was a very long silence. Three and a half years later, in May 2022, I encountered a Sherston man, Pete Evans, at Sheila Evans funeral, and asked if he knew Kat, explaining how I had heard from her. He seemed to know nothing and his face showed no sympathetic expression. I wrote to him later but got no reply.

Then, in February 2024, Kat contacted me.

She hadn't known how to open the file I'd sent until then.

I'd love to meet her sometime, to see how much of Frank is in her DNA, so to speak.

The photograph shows Bert Clifford, Henry Wheeler, and a pensive and unusually dishevelled Frank Thompson, scrumpy in fist, probably fortified with gin. ... at the Carpenters Arms in Sherston ... 1980ish ... and at lunchtime by the angle of the sun.

There follows what little I remember of Frank Thompson ... because I only

knew him a little.

He was never hard to like but you’d have to see someone

regularly and have regular conversations to say you knew and understood

them.

I’m trying to remember the first time I looked at him

closely. I was a stranger in the

Carpenters Arms. I was perhaps

twenty-two or three, so maybe it was in 1972.

I’d entered what I’d imagined to be a quaint old country pub on a sunny

autumn afternoon, expecting to find quaint old agricultural labourers and

instead being almost dazzled by three men in their maybe mid-thirties, very

smart in shiny new but slightly old-fashioned suits and deep film-star suntans,

who were full of laughter and song and were as comfortably relaxed as if they’d

owned the place. They were like young

gods, but drank as if they had no intention of getting old.

To my art-schooled-eyes, Frank looked like an heroic

Michelangelo figure, thinly disguised as a teddy boy. Just now I thought of describing Frank in that moment as a kind of cross between Hercules and Apollo, when they were young and untroubled.

The fashion trends and hair-styles of the

nineteen sixties, which had taken various spectacular forms in popular culture,

had somehow passed un-noticed in the Carpenters Arms. In those days it was an isolated refuge from

modernity. These men had a nineteen-fifties look. That afternoon I was with

some friends who were all younger than these three, and so we didn’t join them

but sat close-by in the very small backroom with its thick ancient walls, tiny

windows, utilitarian bare floors, and puritanically scrubbed and bleached

little tables.

We’d stepped back in

time, quite a long way back, it seemed.

Frank, and his companions Phil Pegler and John Evans filled the room

with raucous jollity, singing tiny snatches of old Dean Martin and Frank

Sinatra songs, so old it suggested an arrested development had held them

lightly somehow for fifteen or twenty years.

The first time Frank and I properly spoke was five or six years later,

maybe 1977 when I went to live at Foxley and began to visit the Carpenters on

Saturday nights and Sunday lunchtimes.

In those five years Frank had become a quieter man, no less

handsome. I came to admire the gentle

courteous nature of him, and to envy his Herculean stature and open gaze.

Yes, a solitary man, happy to be at his own

little table, whose distinguishing character was that unfailing courtesy and

sweetness of voice, and a raw startling beauty.

Now and again we’d take a hand in a game of crib, though I think it

wasn’t a game that interested him much, he was just making up the numbers for

the company perhaps. In those times I

never knew him to show an interest in any thing new.

It might have been Frank who showed me how to

fortify The Carpenters’ notoriously unpalatable scrumpy with a measure of gin. I tried it a few times, was beguiled, but then

quickly realized it wasn’t part of a sustainable lifestyle.

His one small passion was a nostalgia for the

Sherston of his younger years. Oddly, he

carried a small sheath of very old cinema programmes in his jacket pocket and

he once handed them to me to see if I shared his enthusiasm for the films that

had captivated his boyish imagination.

I was working in Malmesbury at the end of the 1970s when a

friend asked me to collect a plumber from a pub in town and drive him out to a

cottage in Minety to fit some new taps.

When I got to the pub to collect the plumber, there was Frank in a crisp

white shirt, open-necked, and with a few tools neatly wrapped in a hessian sack

that lay at his elbow on the table where he drank.

He’d aged a little, was heavier, but was as

placid and confident and courteous as I’d come to take for granted. He had a quiet and gentle way of conversation

that made you feel like old friends from the start. As we drove out towards Minety I quietly

marvelled at the huge plumber’s hands and wondered how this big man might fit

himself in to the intricate corners of modern kitchens.

Not long after that, I saw a rare demonstration of Frank’s

old-fashioned code of honour, which he’d probably learned at the cinema from

Hollywood actors like Alan Ladd or John Wayne.

John Evans, unlike Frank, had become a difficult kind of drunk. Whist John was often the life and soul of the

party, he had few inhibitions and he was always likely to upset the evening

with little or no regard for anyone’s feelings, or for his own safety.

One evening John said something toxically

unkind to Pat, the lady behind the bar in The Carpenters, and it was not for

the first time. Everyone there overheard

it and all were deeply embarrassed.

There was a very short and awkward silence before Frank got up and he quietly but insistently accompanied John from the premises through the back

door, and sent him home via the unlit back yard with a thick lip. He then resumed his seat just as quietly,

asked no praise, made no comment, and the incident was never mentioned

again.

Not long after that, to the surprise of the regulars, Frank

began to show up at The Carpenters with a woman who seemed to match him in fine

looks and sweet temper. She’d have made

an excellent artist’s model for Rubens or Rembrandt or Renoir. She was both picturesque and ornamental, and

how I envied him. Everyone liked her,

and in no time, just as I was leaving Foxley and abandoning The Carpenters, I

heard that they might marry.

Years passed. I’d left

Malmesbury altogether and gone to work in Brighton, but had often drifted back

to visit old friends and family, and would sometimes stay for a day or two to

wander. One morning, just before

catching a bus that began the homeward journey, I discovered Frank sitting in

the back room of the little shop in the Cross Hayes that sold antiques and second-hand furniture .

He was jaundiced and bony and a very sad sight. He made a

space for me beside him and I sat there for a while, knowing from first glance that I

might never see him again, and we talked a little about our changed

worlds. John Evans and Phil

Pegler had not long left the planet, and Frank knew his days were few.

He told me that he was staying in Malmesbury

with Ray and Grace, whose shop it was, and that they were caring for him. Apart from his fatigue, Frank was his old

sweet self, never a trace of complaint or self-pity, nor any bitterness or

regret. All I can remember from the

conversation is my surprise and delight when, in a moment of sweet pathos,

Frank pulled out from his jacket pocket those same old cinema programmes and

offered them for me to show an interest.

I did, and then we parted, myself with as heavy a heart then as now.

Tristan Forward, 24th October 2018, in Tenby.

.png)

.png)

.jpg)