The 100 best nonfiction books: No 94 – Leviathan by Thomas Hobbes (1651)

Thomas Hobbes’s essay on the social contract is both a founding text of western thought and a masterpiece of wit and imagination

According to the 17th-century historian and gossip John Aubrey, Thomas Hobbes “was wont to say that if he had read as much as other men, he should have known no more than other men.” As a great thinker, Hobbes epitomises English common sense and the amateur spirit, and is all the more appealing for deriving his philosophy from his experience as a scholar and man of letters, a contemporary and occasional associate of Galileo, Descartes and the young Charles Stuart, prince of Wales, before the Restoration.

Hobbes himself was born an Elizabethan, and liked to say that his premature birth in 1588 was caused by his mother’s anxiety at the threat of the Spanish Armada:

… it was my mother dear

Did bring forth twins at once, both me, and fear.

Throughout his long life, Hobbes was never far either from the jeopardy of the times (notably the thirty years’ war and the English civil war) or the jeopardy sponsored by the brooding realism and pragmatic clarity of his philosophy. What, asked Hobbes, was the form of politics that would provide the security that he and his contemporaries longed for, but were always denied?

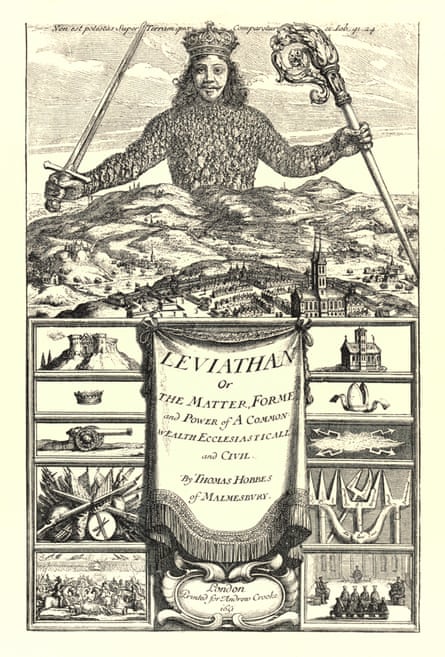

Subtitled The Matter, Forme and Power of a Commonwealth Ecclesiasticall and Civil, Leviathan first appeared in 1651, during the Cromwell years, with perhaps the most famous title page in the English canon, an engraving of an omnipotent giant, composed of myriad tiny human figures, looming above a pastoral landscape with sword and crosier erect.

Thus “the Leviathan” (sovereign power) entered the English lexicon, and Hobbes’s vision of man as not naturally a social being, animated by a respect for community, but a purely selfish creature, motivated by personal advantage, became condensed into his celebrated summary of mankind’s existence as “solitary, poore, nasty, brutish, and short”.

It was Hobbes’s argument that, to ameliorate these conditions, man should adopt certain “Laws of Nature” by which human society would be forbidden to do “that which is destructive” of life, whereby virtue would be the means of “peaceful, sociable and comfortable living.”

The first law of nature is: “every man ought to endeavour peace”. This, he argues, will be a hard goal: the general inclination of all mankind is “a perpetual and restless desire of power after power, that ceaseth only in death”. The second law of nature is: “a man [must] be willing when others are so too … to lay down his right to all things; and be contented with so much liberty against other men, as he would allow other men against himself.” The third law of nature is: “men performe their Covenants made.”

This, in essence, adds up to Hobbes’s social contract, enforced by an external power. Accordingly, members of civil society should enter into a contract to confer their power and strength “upon one Man, or upon an Assembly of men … This done, the Multitude so united in one Person, is called a Common-wealth.” For Hobbes, the contracting of such power is the only guarantee of peace and prosperity: “During the time men live without a common power to keep them all in awe, they are in that condition which is called war; and such a war as is every man against every man.”

Having witnessed the English revolution at first hand, it is war above all that Hobbes most fears. Social warfare empowers mankind’s darkest side: “Force, and fraud, are in war the two cardinal virtues.”

Hobbes is never less than ironical in his attitude to humanity’s appetite for “government”. He had seen too much debate, before and after the execution of Charles I, about the relationship between, citizen, church and state to be anything but pragmatic: “they that are discontented under monarchy, call it tyranny; and they that are displeased with aristocracy, call it oligarchy; so also, they which find themselves grieved under a democracy, call it anarchy, which signifies the want of government; and yet I think no man believes, that want of government, is any new kind of government.”

For Hobbes, the “political community” is paramount, and individuals must surrender themselves for their own further and better protection: “he that complaineth of injury from his sovereign complaineth that whereof he himself is the author; and therefore ought not to accuse any man but himself; no nor himself of injury; because to do injury to one’s self, is impossible.”

As numerous commentators have observed, Leviathan is the founding document of the “social contract theory” that would eventually flourish in the western intellectual tradition. It is also a majestic monument of 17th-century English prose, at once sinewy and vivid:

Riches, knowledge and honour are but several sorts of power.

Hobbes also illuminates his argument with many delicious asides:

The Papacy is not other than the Ghost of the deceased Roman Empire, sitting crowned upon the grave thereof.

This comparison of the papacy with the kingdom of fairies (“that is, to the old wives’ fables in England concerning ghosts and spirits”) is a reminder of the philosopher’s pre-eminent wit and imagination. Combined with the economy, candour and irony of Leviathan as a whole, it marks Hobbes out as one of the truly great writers in the English literary canon. But he is also a giant of western philosophy whose influence can be found in the work of Rousseau and Kant.

Not that his contemporaries understood this. “Hobbism” became a term of opprobrium, Leviathan was publicly burnt as a seditious document, and Hobbes himself spent many of his later years in fear for his life. He died in 1679, suffering from Parkinson’s disease. According to Vanbrugh, on his deathbed he said he was “91 years finding out a hole to go out of this world, and at length found it.” His apocryphal last words were: “I am about to take my last voyage, a great leap in the dark.”

A signature sentence

In such condition [of Warre], there is no place for Industry; because the fruit thereof is uncertain; and consequently no Culture of the Earth; no Navigation, nor use of the commodities that may be imported by Sea; no commodious Building; no instruments of moving and removing such things as require much force; no Knowledge of the face of the Earth; no account of Time; no Arts; no Letters; no Society; and which is worst of all, continuall feare, and danger of violent death; and the life of man, solitary, poore, nasty, brutish, and short.

Three to compare

John Locke: Two Treatises of Government (1690)

David Hume: A Treatise of Human Nature (1739)

Paul Auster: Leviathan (1992)

.jpg)