this drawing is a copy, attributed to John Linnell

The Man Who Taught Blake Painting in his Dreams (after William Blake)

c.1825

I used the following link to source Laurence Binyon's text

The Drawings and Engravings of

William Blake, by William Blake

Introduction by Laurence Binyon

FOR the sale of the Linnell collection of drawings, prints and books by Blake, the great room at Christie’s was full to overflowing. It was March of 1918. Copies of the Songs of Innocence, of the Marriage of Heaven and Hell; the set of water-colour designs for The Book of Job; the famous century of Dante illustrations; single drawings and rare prints; all were fetching or going to fetch hitherto unparalleled prices.

Competition ran high, the excitement of the bidders was infectious. In the middle of the sale Lot 171 was announced; and observers on the edge of the crowd could see, lifted high in the hands of the baize-aproned, impassive attendant, a human mask, conspicuous in its white plaster. It was the life-mask of William Blake; and as those tense features were carried duly along the knots of dealers and bidders, who, pencil and catalogue in hand, threw up at it an appraising glance, the Ironic Muse could surely not have forborne a smile. The auctioneer invited bids, collecting from various quarters those imperceptible nods which give to auctions an air of magic and conspiracy; and still the white mask, with the trenchant lip-line and the full, tight-closed eyes, was held up and offered to every gaze, turned now this way and now that.

It seemed to be the most living thing in the room; as if the throng of curious watchers, murmuring among themselves, and the auctioneer himself, were mere shadows engaged in a shadowy chaffering. It seemed to me that, next moment, those eyes would blaze open, seeing, not us, but some vision of celestial radiance; and that all who could not share that vision must dissolve into their native insignificance.

Sentences floated through my brain: “I should be sorry if I had any earthly fame, for whatever natural glory a man has is so much detracted from his spiritual glory. I wish to do nothing for profit; I want nothing; I am quite happy.” “Painting exists and exults in immortal thoughts.” “Art is a means of conversing with Paradise.”

I remembered how Blake died singing hymns of joy. And I thought of his “madness”; and suddenly it appeared as if the world, with its mania for possessing things, and its commercial values for creations of the spirit, were really insane, and the spirit inspiring Blake the only sane thing in it.

Competition ran high, the excitement of the bidders was infectious. In the middle of the sale Lot 171 was announced; and observers on the edge of the crowd could see, lifted high in the hands of the baize-aproned, impassive attendant, a human mask, conspicuous in its white plaster. It was the life-mask of William Blake; and as those tense features were carried duly along the knots of dealers and bidders, who, pencil and catalogue in hand, threw up at it an appraising glance, the Ironic Muse could surely not have forborne a smile. The auctioneer invited bids, collecting from various quarters those imperceptible nods which give to auctions an air of magic and conspiracy; and still the white mask, with the trenchant lip-line and the full, tight-closed eyes, was held up and offered to every gaze, turned now this way and now that.

It seemed to be the most living thing in the room; as if the throng of curious watchers, murmuring among themselves, and the auctioneer himself, were mere shadows engaged in a shadowy chaffering. It seemed to me that, next moment, those eyes would blaze open, seeing, not us, but some vision of celestial radiance; and that all who could not share that vision must dissolve into their native insignificance.

Sentences floated through my brain: “I should be sorry if I had any earthly fame, for whatever natural glory a man has is so much detracted from his spiritual glory. I wish to do nothing for profit; I want nothing; I am quite happy.” “Painting exists and exults in immortal thoughts.” “Art is a means of conversing with Paradise.”

I remembered how Blake died singing hymns of joy. And I thought of his “madness”; and suddenly it appeared as if the world, with its mania for possessing things, and its commercial values for creations of the spirit, were really insane, and the spirit inspiring Blake the only sane thing in it.

I.

A subtle fluid streams through Blake’s work, which has in it the germ of intoxication; hence people find it hard to judge of it without a certain extravagance, either of admiration or repulsion. Possibly indeed a quite “sane” estimate of it misses something of its essence. But, after all, he is an artist among the artists of the world, with affinities among them, if few of these are to be found among those of his own race, and fewer still among those of his own time. There is no need to judge him by a strange and special standard, as if he were a wholly isolated phenomenon. He is one of the greatest imaginative artists of England.

The first edition of “The Golden Treasury” contained none of Blake’s poems: now his songs are in every anthology. He has come into his kingdom as a poet. As a seer and as a quickening influence on the thought of later generations he is recognized. As an artist, also, he has of late years begun to receive more general homage. But Blake’s art, in its great qualities as in its frequent blemishes and deficiencies, is still not understood and appreciated as it should be; and chiefly because it is little known. Yet it is as painter, draughtsman and engraver that Blake is greatest. Nothing perhaps in his pictorial art quite matches the aerial radiance and felicity of his best songs. But nothing in his poetry has the sustained grandeur of the Job engravings, or of a whole series of splendidly imagined designs.

We are here concerned with Blake solely as an artist. And first let me lay stress on his range and inventiveness as a technician. Were there no mystical ideas or original imagination to attract us to his work, we could still admire the artist who, in a time when the fashionable academicians hardly seemed to know of the existence of any art but that of painting in oils, engraved his own designs, painted in water-colours and in distemper, invented two methods of etching in relief, revived (doubtless without consciousness of any predecessor) the “monotype,” engraved original woodcuts, and made at least one experiment in lithography. He was also the printer of his own “illuminated” books. If Blake had had the means and opportunity of being a sculptor, I feel sure that he would have rejected with scorn the accepted modern way of modelling a figure to be copied in marble by workmen, but would have taken a chisel and a block of stone and gone to work like the carvers of the Gothic cathedrals.

But I am far from thinking that, if Blake had had an empty mind and dull imagination, these merits of the innovator and technician would have sufficed of themselves to give him a hold on the world’s memory. Indeed he would not have been driven to find new methods if he had been interested in technique merely for its own sake. He had intense ideas and a peculiar imagination which he wanted to express, and he found the methods in fashion inadequate or uncongenial. The youth of that day who burned with ambition to paint “history” — the term was comprehensively used in the eighteenth century — would naturally aspire above all things to use the medium of oils on a large scale. But Blake hated the oil medium. He said absurd things about the great masters of oil painting — Rubens and Rembrandt and Reynolds — but he was instinctively right in discarding it himself.

He made many experiments with one medium or another, though he never arrived at a quite successful solution of his problem, except in water-colour; and here, too, he made experiments, discovering, by a mixture of painting and printing, a way of giving force to the medium adequate to the power of his grandest designs. And he employed similar means for enriching the books which he engraved and printed himself, giving his work a peculiarly original character. As an engraver, he only arrived after long years and towards the end of his life in finding a congenial method. In all this he was not interested in technique for its own sake; he was seeking the expressive counterpart of his imaginative ideas. But neither would these imaginative ideas give him rank as an artist, were they not directly expressed through pictorial design.

We are here concerned with Blake solely as an artist. And first let me lay stress on his range and inventiveness as a technician. Were there no mystical ideas or original imagination to attract us to his work, we could still admire the artist who, in a time when the fashionable academicians hardly seemed to know of the existence of any art but that of painting in oils, engraved his own designs, painted in water-colours and in distemper, invented two methods of etching in relief, revived (doubtless without consciousness of any predecessor) the “monotype,” engraved original woodcuts, and made at least one experiment in lithography. He was also the printer of his own “illuminated” books. If Blake had had the means and opportunity of being a sculptor, I feel sure that he would have rejected with scorn the accepted modern way of modelling a figure to be copied in marble by workmen, but would have taken a chisel and a block of stone and gone to work like the carvers of the Gothic cathedrals.

But I am far from thinking that, if Blake had had an empty mind and dull imagination, these merits of the innovator and technician would have sufficed of themselves to give him a hold on the world’s memory. Indeed he would not have been driven to find new methods if he had been interested in technique merely for its own sake. He had intense ideas and a peculiar imagination which he wanted to express, and he found the methods in fashion inadequate or uncongenial. The youth of that day who burned with ambition to paint “history” — the term was comprehensively used in the eighteenth century — would naturally aspire above all things to use the medium of oils on a large scale. But Blake hated the oil medium. He said absurd things about the great masters of oil painting — Rubens and Rembrandt and Reynolds — but he was instinctively right in discarding it himself.

He made many experiments with one medium or another, though he never arrived at a quite successful solution of his problem, except in water-colour; and here, too, he made experiments, discovering, by a mixture of painting and printing, a way of giving force to the medium adequate to the power of his grandest designs. And he employed similar means for enriching the books which he engraved and printed himself, giving his work a peculiarly original character. As an engraver, he only arrived after long years and towards the end of his life in finding a congenial method. In all this he was not interested in technique for its own sake; he was seeking the expressive counterpart of his imaginative ideas. But neither would these imaginative ideas give him rank as an artist, were they not directly expressed through pictorial design.

II.

Blake was a boy of sixteen when on his first original engraving, “Joseph of Arimathea among the rocks of Albion,” he inscribed these words: This is One of the Gothic Artists who Built the Cathedrals in what we call the Dark Ages, Wandering about in sheep skins and goat skins, of whom the World was not worthy. Such were the Christians in all Ages. Already we can see into Blake’s mind and have a glimpse of the world of ideas in which it was to dwell throughout his life. Long months of solitary work and contemplation in the most impressionable years of boyhood among the soaring pillars and supine effigies of the Abbey had saturated his spirit with the forms of Gothic art. There was no architecture for him but Gothic architecture thereafter. “Grecian is mathematic form,” he said, “Gothic is living form.” Gothic is a pregnant word in this inscription. Blake was fascinated by the legend of Saint Joseph of Arimathea and his missionary voyage to Britain. Some years later he was to make a small colour-print, now excessively rare, of Saint Joseph preaching to the Britons.

The legend appealed to Blake’s profound attachment to his country, whose mythic past, as he read it in Milton’s History, he loved to idealize, and whose genius he symbolized in his own mythology as the Giant Albion, “the Patriarch of the Atlantic.”

In the Descriptive Catalogue he writes of his “visionary contemplations relating to his own country and its ancient glory, when it was, as it again shall be, the source of learning and inspiration.” He conceived of the Druids and the Ancient Bards of Britain as of the same company as the Prophets and Patriarchs of Israel. Jerusalem, the ideal city of the Imagination, was to be built in “England’s green and pleasant land.”

Finally we may underline in the inscription I have quoted the words Artist and Christian. To Blake these were synonymous. No one could be a Christian who was not an artist. At sixteen, then, Blake seems already possessed of the master conceptions of his mature thought and art. And the subject-matter of his paintings is just what we should expect from a mind preoccupied with such conceptions. Classic mythology, one of the main sources of motives for ambitious efforts in composition since the time of the Renaissance, is almost excluded.

The Hecate (Plate 32) seems imagined from Shakespearean phrases and allusions, rather than intended to figure forth a classic goddess.

We reproduce, for its interest (Plate 82), one of Blake’s few excursions into Greek fable, his Judgment of Paris; and here also he is anything but dependent on classic traditions of art, and produces a scene of “Gothicized” atmosphere, with comic touches like the name of Paris so carefully engraved on his dog’s collar.

Avoiding the Greeks and Romans, Blake chose themes of national or Biblical inspiration. A born myth-maker, he went on to invent a mythology of his own, in which mystic ideas predominated, but in which such symbolic names as Albion and Jerusalem tell of the two soils in which his imagination was rooted. But his art was happier when it sought expression through forms and legends which belong to the common heritage of Europe rather than to his private mental world.

The early pictures and drawings are often inspired by English history. Gray’s studies in Norse poetry attracted him, as did Ossian: an illustration to “The Bard” was one of his earliest exhibited works. ( Work lost ... sketch below )

Later on he even took themes from contemporary England, and made “mythological” pictures of Pitt and Nelson as heroes of his nation.

Above ... The Spirit Of Pitt Guiding Behemoth

He made many sets of designs from Milton. His illustrations to “L’ Allegro” and “Il Penseroso” were in the Crewe collection, and are now in America.

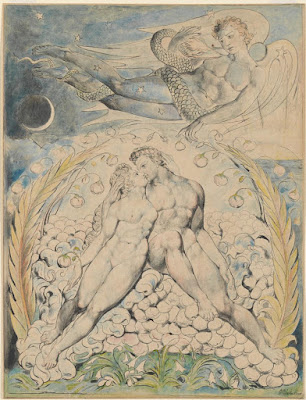

The Butts set of nine designs from “Paradise Lost” is in the Boston Museum; other versions are in various collections.

Eight illustrations to “Comus” are also at Boston.

Twelve designs from “Paradise Regained” (once Linnell’s ) are in Mr. Riches’ collection.

the picture below is from a set bequeathed to the fitzwilliam museum by mister riches ...

He illustrated Young’s “Night Thoughts”

and Gray’s “Poems, both very fully;

and Blair’s “Grave,”

and the “Pilgrim’s Progress,”

and some of Shakespeare;

and made a hundred drawings for Dante.

But, apart from his own mystical inventions, his most constant source is the Bible.

The book of Job attracted him early, and became his favourite and his greatest theme. Many of his best and most original paintings and drawings, however, are drawn from the New Testament.

To return for a moment to the engraving of Joseph of Arimathea. The figure of the Saint is taken straight from a figure in Michelangelo’s fresco of the Crucifixion of St. Peter, though the drawing which served as a model was probably not a design of the master’s own hand, but one of the innumerable highly-finished school copies made after the picture. It took Blake’s fancy; he gave it a new name and he placed it in a background of his own imagining, on a rocky cliff beside the sea.

The translation of a massive Michelangelo type into a Gothic atmosphere is characteristic of Blake’s art. One of the sources of dissatisfaction in Blake’s drawings is the incongruity between heavily-muscled nudes, taken from Renaissance models, though realized as a whole in almost rudimentary fashion, and the ethereal movement and long lines of his draped figures, taken from memories of Gothic sculpture. In his thought there is a similar dualism; intense spirituality and the assertion of the glory of the body and the holiness of its passions.

In the early engraving Glad Day, made in 1780, the nude form is of a type which really seems to express the spirit through the body: but later Blake took over forms from prints he had seen of Michelangelo’s latest work, like the Last Judgment, and made a sort of convention of the elaborated play of developed muscles on his nude forms.

We cannot doubt that he recognized the profoundly spiritual element in the great Florentine; but how much he would have profited could he have seen with his own eyes, instead of through poor translations, the Prophets and the Sibyls, and the Adam, and the glorious athletes of the Sistine ceiling! Having nothing of the severe Florentine discipline in draughtsmanship behind him, and being besides incapable by temperament of emulating such mastery, he adopted from the outside a set of forms, attitudes and gestures which we find repeated again and again through his work; the naked body being never drawn for its own sake but as the symbol of definite desires, ideas, and energies.

Hence there is often a kind of cheapness or incompleteness in Blake’s forms, which we forgive because of the inspired energy with which he uses them. He copied his visions, and maintained that these were “organized and minutely articulated beyond all that mortal and perishing nature can produce.” His copies, we infer, were far from perfect. I do not know whether others have the same experience, but I find that Blake’s works seem to dilate and gather beauty in recollection, so that often the actuality, when seen again, disappoints. They exert a greater power over the mind than the eye.

In the early engraving Glad Day, made in 1780, the nude form is of a type which really seems to express the spirit through the body: but later Blake took over forms from prints he had seen of Michelangelo’s latest work, like the Last Judgment, and made a sort of convention of the elaborated play of developed muscles on his nude forms.

We cannot doubt that he recognized the profoundly spiritual element in the great Florentine; but how much he would have profited could he have seen with his own eyes, instead of through poor translations, the Prophets and the Sibyls, and the Adam, and the glorious athletes of the Sistine ceiling! Having nothing of the severe Florentine discipline in draughtsmanship behind him, and being besides incapable by temperament of emulating such mastery, he adopted from the outside a set of forms, attitudes and gestures which we find repeated again and again through his work; the naked body being never drawn for its own sake but as the symbol of definite desires, ideas, and energies.

Hence there is often a kind of cheapness or incompleteness in Blake’s forms, which we forgive because of the inspired energy with which he uses them. He copied his visions, and maintained that these were “organized and minutely articulated beyond all that mortal and perishing nature can produce.” His copies, we infer, were far from perfect. I do not know whether others have the same experience, but I find that Blake’s works seem to dilate and gather beauty in recollection, so that often the actuality, when seen again, disappoints. They exert a greater power over the mind than the eye.

Blake’s conception of human form and manner of drawing, taken by themselves, are often hardly different from what we find in ambitious contemporaries like James Barry and others now forgotten, whom he admired. But in most of Blake’s work, even when he is not at his best, we are conscious at once of something in it which makes an immense difference; something which is alive, which excites and challenges our spirits. It is a demonic power, flowing from a mysterious source. And of a piece with this power is Blake’s gift for spontaneous design, which contrasts with the compositions of most artists by its extraordinary directness of attack. He is a great, because a passionate designer; and considering his limited repertory of forms his instinctive arrangements of them show surprising resource of invention. If he uses a basis of symmetry, as he often does, he does not learnedly disguise it, as other artists have done, but employs it to its utmost value, almost diagrammatically, as in The Sacrifice of Jephthah (in the Graham Robertson collection),

or as in some of the Job engravings, or the Angels hovering over the Body of Jesus (Plate 77).

He uses the device of repetition with the same bold and naked reliance on its force, as in the Stoning of Achan (Plate 46) with its repetition of lifted arms.

The Job series alone suffices to show what a master of imaginative design Blake was: and the reproductions in this book illustrate many drawings which for creative power are hardly rivalled in English art.

or as in some of the Job engravings, or the Angels hovering over the Body of Jesus (Plate 77).

He uses the device of repetition with the same bold and naked reliance on its force, as in the Stoning of Achan (Plate 46) with its repetition of lifted arms.

The Job series alone suffices to show what a master of imaginative design Blake was: and the reproductions in this book illustrate many drawings which for creative power are hardly rivalled in English art.

Blake is not among the great colourists, as we usually understand the term; yet his colour has fascinations of its own. It is sometimes powerful, rarely subtle. He does not select and make a harmony of his selection. He will take all the tints of the rainbow at once: but just as in his design, his impetuous audacity and directness carry off what in one less impassioned would be a mere revelry of varied colour. Sometimes his colour is careless, or unpleasant, but sometimes quite lovely, with a delicate, throbbing aerial flush

III.

The poet sees the world not as a series of aspects but as related energies and movements. Blake was a poet when he painted as when he wrote. The energies and movements which underlie and cause the phenomena of life were his pictorial themes; and these he personified, as the primitive imagination of mankind has personified the forces that it saw or divined around it. When Gray writes

From Helicon’s harmonious springs

A thousand rills their mazy progress take:

The laughing flowers, that round them blow,

Drink life and fragrance as they flow,

what picture is made in Blake’s mind? He sees the flowers, in form such as never grew on earth, as the nest or cradle of little fairy-shapes which bend down to scoop up the water from the stream and drink it with ecstatic gestures.

One might multiply indefinitely similar instances in which what for the reader is a metaphor taken for granted and almost lost in the habits of language, bursts for Blake into the vivid image of its original meaning. See what he has made of Shakespeare’s image of Pity in “Macbeth” (Plate 36).

One might multiply indefinitely similar instances in which what for the reader is a metaphor taken for granted and almost lost in the habits of language, bursts for Blake into the vivid image of its original meaning. See what he has made of Shakespeare’s image of Pity in “Macbeth” (Plate 36).

This natural kinship with primitive imagination goes with an extraordinary zest for the elemental. In “The Gates of Paradise” Blake has depicted (Plates 17, 18) the Elements of Earth, Water, Air and Fire

how much more he seems to sympathize with the released and triumphant flames than with the terrified efforts of the burning city’s inhabitants to save their treasures! How magnificent the swirl of the flames behind the winged Satan and the recumbent Eve (Plate 38)

and in the Elijah (Plate 42)!

I do not think that in the whole art of Europe there is anyone who has painted fire and flame so splendidly as Blake. He loves to give to his figures the rushing movement of wind, and communicates the sense of movement so vividly that we seem to share in it. Indeed it is one of the chief exhilarations of his art that we seem in contemplating or remembering it to be endowed with ideal faculties, transcending the body’s limitations and such as we enjoy only in our dreams. Movement controls his drawing.

Wonderful again is Blake’s apprehension of the vast and starry spaces of night (Plate 23).

Torrents and waterfalls he never saw; but how fine is the movement of heavy water in the small drawing of the sea (Plate 50), and of gliding streams whenever he draws them!

With this zest for the elemental and his instincts of the Primitive, Blake seems always to be seeking to get back to the beginning. He did not, indeed, as has been done in our day, seek in art to get back to the savage; but his mind was full of a glorious mythic Britain in the past, and seeing the mind of his own age overlaid and choked with the decayed and dead traditions of the Renaissance, he sought behind all that for gleams of inspiration in what remained of ancient English painting and sculpture. But, as he somewhere says, he could not help being infected at times by his own age and things he had seen, and we see the traces of infection in his less happy efforts, more plainly doubtless than he was himself aware of.

IV.

At the opposite end of the world, in a country then hardly known to English people except as a sort of legend, there was living in Blake’s time an artist with whom he has some strange affinities. Soga Shohaku was a painter of Kyoto, who died in 1782. The popular movement in Japanese painting of the day was toward naturalism, and the successful master of that movement was Okio, whose works were everywhere admired, copied, and sought after.

Shohaku hated naturalism and derided Okio, as Blake derided Reynolds. He longed to bring back the great days of the fifteenth century, when masters of his own Soga family had painted in inspired, impulsive strokes of the ink-charged brush the spiritual heroes dear to the votaries of the Doctrine of Contemplation. Shohaku was poor, arrogant, and was thought insane.

His mind dwelt in a world which, for all the obvious differences, had a fundamental affinity with the mental world of Blake; the world impregnated with the bold paradoxes of Lao-tzu and his followers, asserting the infinite liberty of the spirit, contemning routine, ceremony, great possessions, and all literal interpretations of sacred books, believing in forgiveness and in a fluid mind. Shohaku, like Blake, was infected by his own age, and the force of his style often touched the extravagant and grotesque.

Shohaku hated naturalism and derided Okio, as Blake derided Reynolds. He longed to bring back the great days of the fifteenth century, when masters of his own Soga family had painted in inspired, impulsive strokes of the ink-charged brush the spiritual heroes dear to the votaries of the Doctrine of Contemplation. Shohaku was poor, arrogant, and was thought insane.

His mind dwelt in a world which, for all the obvious differences, had a fundamental affinity with the mental world of Blake; the world impregnated with the bold paradoxes of Lao-tzu and his followers, asserting the infinite liberty of the spirit, contemning routine, ceremony, great possessions, and all literal interpretations of sacred books, believing in forgiveness and in a fluid mind. Shohaku, like Blake, was infected by his own age, and the force of his style often touched the extravagant and grotesque.

It is not for nothing that of all our artists Blake is probably the one who makes the strongest appeal to the cultivated Japanese. (A book on Blake by M. Yanagi was published in Japan in 1915). Lovers of art in the Further East would never dream of condemning Blake’s “incorrect drawing,” they would take his arbitrary proportions as part of his artistic nature, just as in the case of the masters of their own classic art. Not looking for complete representation in a picture, but for “inventive and visionary conception,” they would not find Blake eccentric, at any rate in style.

Can it be true that Blake was, as he claimed, “taken in vision into the ancient republics, monarchies and patriarchates of Asia” ?

Can it be true that Blake was, as he claimed, “taken in vision into the ancient republics, monarchies and patriarchates of Asia” ?

On the back of Mr. Morse’s wonderful drawing of The Rainbow over the Flood (see above Plate 50), there is a pencil drawing of a human figure with an elephant’s head, holding on his knee a similar-headed child. I have heard that this was meant for a spiritual portrait of someone. But one would say at once; This is the Indian god Ganesha.” And common-sense confidently concludes that Blake had seen some statue of Ganesha, and remembered it.

But then we recall that page in “Jerusalem” (Plate 63)

where the great man-headed, bearded bulls seem to have stepped from the porches of the ruined palace of Nineveh: and dates confront us with the fact that it was not till over twenty years after Blake’s death that Rossetti saw these alabaster monsters being “hoisted in” at the doors of the British Museum:

in his lifetime they were still buried under the Mesopotamian sands and unknown to all the world.

V.

Had Blake seen and studied medieval manuscripts when he set about making the “Songs of Innocence “?

It is hardly possible that he could have escaped seeing, and delighting in, illuminated missals and breviaries. And had he not been a trained engraver, I think that in default of a printer and publisher he would have written out copies of the Songs and decorated them with his brush. But having the resources of his craft at his command he invented a way of multiplying copies, though, as the colouring of each page was done by hand, the labour involved was hardly less than if he had been both scribe and illuminator.

It is hardly possible that he could have escaped seeing, and delighting in, illuminated missals and breviaries. And had he not been a trained engraver, I think that in default of a printer and publisher he would have written out copies of the Songs and decorated them with his brush. But having the resources of his craft at his command he invented a way of multiplying copies, though, as the colouring of each page was done by hand, the labour involved was hardly less than if he had been both scribe and illuminator.

The method invented for the needs of the occasion, and used later for most of the Prophetic Books, was that of etching both text and decoration in relief. “Instead of etching the blacks, etch the whites,” is Blake’s memorandum. It was a less laborious way of producing the effect of a woodcut; an anticipation in fact of the process-block. But the page as first printed was not intended to be complete; it was merely the foundation of a page finished in colour by the brush. For the printing he chose a tawny, a reddish, a green or a blue tint. In the tiny plates of “There is No Natural Religion”— which was possibly the earliest of the whole series — more than one colour was dabbed on to the copper;

... so too in certain pages of “Urizen”; and probably in more cases than has generally been admitted; though as a rule the printing was done in one colour only. The hand-colouring of some copies was in transparent tints, of others in opaque colour, with a sort of granulated impasto, an effect chiefly due, perhaps, to the printing.

and 12

reproduce the same design from “Thel,” and illustrate the entirely different effect obtained by these different methods. Copies of the Songs and of the Prophetic Books vary greatly. A detailed account of the various copies known is given in Mr. Keynes’ invaluable Bibliography.

In decorative combination of text and design the Songs are perhaps the most successful of the books, though not all the pages are happy. But in the history of book-printing and book-decoration these rare volumes are an interesting link between the illuminated manuscripts of the Middle Ages and the revival of the “beautiful book” by William Morris.

The pages reproduced give some idea of the range of design to be found in the books, which contain some of Blake’s most striking, some of his strangest, and some of his least attractive work. The “Jerusalem,” which is usually uncoloured, has the most impressive pages of all. Begun in 1804, it was not finished, as Mr. Keynes has shown, till 1818. With the “Milton” it makes a second group, separated from the rest by an interval of some years.

It is remarkable that in the two latest of the main group of Prophetic Books, “Ahania”

and the “Book of Los,”

each of which is known only by a single copy, the ordinary method of etching is employed for the text, and the colour for the design separately applied to the plates. This unexpected experiment was not felicitous, and the relief-process was resumed in “Milton” and “Jerusalem,” though in both of these we find a greatly increased use of the “white-line” method of working from the lights to the darks, in which the effects to be obtained later in the “Virgil” wood-cuts are anticipated. Some pages of “Jerusalem,” e.g., page 28

and page 33,

seem to be largely graver-work what Blake called “woodcutting on pewter” though probably combined with the use of acid.

It is remarkable that in the two latest of the main group of Prophetic Books, “Ahania”

and the “Book of Los,”

each of which is known only by a single copy, the ordinary method of etching is employed for the text, and the colour for the design separately applied to the plates. This unexpected experiment was not felicitous, and the relief-process was resumed in “Milton” and “Jerusalem,” though in both of these we find a greatly increased use of the “white-line” method of working from the lights to the darks, in which the effects to be obtained later in the “Virgil” wood-cuts are anticipated. Some pages of “Jerusalem,” e.g., page 28

and page 33,

seem to be largely graver-work what Blake called “woodcutting on pewter” though probably combined with the use of acid.

The designs in the Prophetic Books suffer less than the text of them from the difficulty of deciphering the code of Blake’s private symbolism. We can enjoy the pictorial energy in them for its own sake. But the creatures of his Myth have not the vitality of the figures which belong to the world’s imagination, as we see by comparison with the splendid drawings which were made by Blake at the same period of his life.

VI.

Charles Lamb said that his real opera were not the essays that his leisure hours produced, but the great folios, filled by his laborious pen, on the shelves of the India House. So might Blake have pointed to the series of line-engravings, done after other men’s designs, which occupied so great a proportion of his working days. Had he done nothing original, his name would still be dimly preserved in books of reference among those of serviceable, obscure engravers of the English school.

His original prints were produced at intervals, sometimes of many years. As everyone knows, Blake was apprenticed to James Basire, a good man at his craft, but not notable or distinguished. Two years after his apprenticeship had begun, in 1773, Blake produced his first original engraving, the Joseph of Arimathea, which we have already described and discussed. Blake was a boy of sixteen when he engraved this plate. If there is incongruity in the matter of the design, there is incongruity also in the technical means. We feel conscious both of impulse and impediment; a desire to use the graver on the copper as a free instrument of expression, impeded not so much by want of skill as by the impositions of habit and professional training.

Since the time of Dürer and the Little Masters, the art of line-engraving had been made over to the business of reproducing the work of painters and draughtsmen. It had become an art of translation. The tones of the painter had to be translated into the lines of the engraver. In the latter part of the eighteenth century the usual procedure was to etch the ground-work of the print and then go over the whole with the graver, adding the finer and more delicate lines required. The use of the acid as a preliminary saved much labour, but it meant the loss of that brilliant purity and freshness which is so delightful in the work of earlier men like Goltzius, or the fine group of engravers who worked for Rubens, or the French masters of the portrait.

Mechanical devices for translation of tone like the famous “lozenge and dot,” had become a tradition. All through his life we see Blake, in his original line-engravings, striving to get free from the encumbrance of professional routine, seeking for a really expressive method of using his tools, and never quite satisfied, till towards the end of his life he does really seem to find himself.

Mechanical devices for translation of tone like the famous “lozenge and dot,” had become a tradition. All through his life we see Blake, in his original line-engravings, striving to get free from the encumbrance of professional routine, seeking for a really expressive method of using his tools, and never quite satisfied, till towards the end of his life he does really seem to find himself.

In 1780 Blake had produced the print called Glad Day;

(CAN'T FIND THE 1780 VERSION, ONLY THE 1810, above)

the figure of a young man alighting on a hill with outstretched arms, a caterpillar at his feet and a gross moth flying from the dawn. Here there is a complete recoil from professional methods. There is no elaboration, no cross-hatching; it is little more than outline. With a gain in spontaneous directness, it remains tentative and meagre. The artist seems to have felt its deficiencies, for he used the same design some ten years later for a coloured relief-etching (Plate 34).

This, like the Joseph of Arimathea preaching, which I have already mentioned, is known by but one or two copies. The flaming richness of the colouring had darkened, but has now been restored. To 1793 belong two contrasted works in original engraving: the pair of large engravings Job’s Complaint

and The Death of Ezekiel’s Wife;

and the little book of eighteen prints called “The Gates of Paradise.”

Mr. Graham Robertson owns the finished Indian-ink drawings for the Job (Plate 16)

and the Ezekiel.

Miss Carthew possesses a study for the Job, with a different arrangement of the figures; and slighter pencil studies are in the Print Room.

The engravings of these two subjects are ambitious, and Blake employed all the skill he had learnt in his profession. He never again engraved a design on so large a scale. The two prints show a certain effort to escape from the routine of training, especially the Ezekiel, where there is less of the heavy cross-hatching and more reliance on parallel strokes of the graver; but they are, after all, translations from tone into line, and as translations are not very felicitous. Blake had done the utmost he could with the experience he had learnt in the elaborate method. But he needed better models, and these as yet he had not studied, though he had certainly seen prints by Dürer and his school.

(CAN'T FIND THE 1780 VERSION, ONLY THE 1810, above)

the figure of a young man alighting on a hill with outstretched arms, a caterpillar at his feet and a gross moth flying from the dawn. Here there is a complete recoil from professional methods. There is no elaboration, no cross-hatching; it is little more than outline. With a gain in spontaneous directness, it remains tentative and meagre. The artist seems to have felt its deficiencies, for he used the same design some ten years later for a coloured relief-etching (Plate 34).

This, like the Joseph of Arimathea preaching, which I have already mentioned, is known by but one or two copies. The flaming richness of the colouring had darkened, but has now been restored. To 1793 belong two contrasted works in original engraving: the pair of large engravings Job’s Complaint

and The Death of Ezekiel’s Wife;

and the little book of eighteen prints called “The Gates of Paradise.”

Mr. Graham Robertson owns the finished Indian-ink drawings for the Job (Plate 16)

and the Ezekiel.

Miss Carthew possesses a study for the Job, with a different arrangement of the figures; and slighter pencil studies are in the Print Room.

The engravings of these two subjects are ambitious, and Blake employed all the skill he had learnt in his profession. He never again engraved a design on so large a scale. The two prints show a certain effort to escape from the routine of training, especially the Ezekiel, where there is less of the heavy cross-hatching and more reliance on parallel strokes of the graver; but they are, after all, translations from tone into line, and as translations are not very felicitous. Blake had done the utmost he could with the experience he had learnt in the elaborate method. But he needed better models, and these as yet he had not studied, though he had certainly seen prints by Dürer and his school.

In an almost completely contrasted method are the little plates of “The Gates of Paradise.” The designs are sketched on the copper, and though the graver-work betrays a certain habit of formality, increased by the dry printing of the time, the general impression is of a spontaneous lightness. Nevertheless, we feel that etching or dry-point would have been a happier medium.

In 1796 and 1797 Blake engraved the illustrations to Young’s “Night Thoughts.”

In 1796 and 1797 Blake engraved the illustrations to Young’s “Night Thoughts.”

He had made altogether five hundred and thirty-seven drawings in colour-wash and pen for this poem, on folio sheets into which the printed pages were inlaid, the margins being filled with the designs: but only forty-three were engraved. The drawings now belong to Mr. W. A. White, of Brooklyn: they are naturally unequal, but some of them (not engraved) seemed to me very beautiful when I saw them.

It is by these illustrations and those to Blair’s “Grave” (engraved by Schiavonetti)

that Blake was best known to the public of his time, since both were published, unlike most of his work, in the ordinary way, through a bookseller. But though none could fail to be struck by their imaginative power and invention, neither series ranks with Blake’s finest achievements. Nor in the “Night Thoughts” has he succeeded in finding a satisfying manner of using the burin.

In the drawings the natural fire and sweep of the pen-line and the light washes of bright colour stimulate the eye; they have the virtue of a spontaneous sketch; but translated into engraved lines they are tamed, and the forms are apt to look empty.

that Blake was best known to the public of his time, since both were published, unlike most of his work, in the ordinary way, through a bookseller. But though none could fail to be struck by their imaginative power and invention, neither series ranks with Blake’s finest achievements. Nor in the “Night Thoughts” has he succeeded in finding a satisfying manner of using the burin.

In the drawings the natural fire and sweep of the pen-line and the light washes of bright colour stimulate the eye; they have the virtue of a spontaneous sketch; but translated into engraved lines they are tamed, and the forms are apt to look empty.

1810 is the date of the Canterbury Pilgrims, engraved by Blake after his own picture. This he claimed to be in the manner of Diirer and the old engravers; but though there is a sort of experimental archaism in it, the effect is laboured and dry.

Eight years after this he met the young Linnell, who turned his attention to engravings of the school of Marcantonio;

and now at last he was led to study the kind of model which he had so long been wanting. The fruit of this new study is seen in the “Illustrations to the Book of Job.”

Here at last, at nearly seventy years of age, Blake has found felicity. It is our good fortune that these, the noblest series of designs which he ever made, are by far the finest of his original prints. There is no comparison between these and his earlier plates. They are the greatest work in original line-engraving that modern Europe has produced since the sixteenth century; and in the realm of imaginative design there is very little in English art that we can place above or beside them.

The Job series gained by the unusual patience that Blake, by nature so impatient, devoted to their production. Not only had the study of Job been for long years in his mind, but the studies still existing for some of the compositions show how he matured his conceptions and gradually improved on them. By comparison such work as the designs for the “Night Thoughts” and Gray’s Poems seem hasty improvisations.

and now at last he was led to study the kind of model which he had so long been wanting. The fruit of this new study is seen in the “Illustrations to the Book of Job.”

Here at last, at nearly seventy years of age, Blake has found felicity. It is our good fortune that these, the noblest series of designs which he ever made, are by far the finest of his original prints. There is no comparison between these and his earlier plates. They are the greatest work in original line-engraving that modern Europe has produced since the sixteenth century; and in the realm of imaginative design there is very little in English art that we can place above or beside them.

The Job series gained by the unusual patience that Blake, by nature so impatient, devoted to their production. Not only had the study of Job been for long years in his mind, but the studies still existing for some of the compositions show how he matured his conceptions and gradually improved on them. By comparison such work as the designs for the “Night Thoughts” and Gray’s Poems seem hasty improvisations.

Moreover he made two sets of elaborate coloured drawings; in 1822, for Butts,

and in 1823-5, for Linnell,

before he set to work on the engravings. I have seen both these sets of drawings (the former set was sold at the Crewe sale in 1903; both are now in America) and though some judges have thought differently, the engravings represent, to my mind, the finest and completest forms of the designs. They seem to me throughout to be superior to the drawings.

There exists, indeed, one painting which is a modification of the sixth plate of the engravings and which is certainly superior to the print; but this painting, which is in tempera on panel, must surely have been of later date than the engraving. It belonged to Sir Charles Dilke and is now in the Tate Gallery (Plate 95).

Here the shape of the design is altered: Satan has wide, out-spread wings, and the sullen sunset splendour of the colouring seems to be in its original condition.

and in 1823-5, for Linnell,

before he set to work on the engravings. I have seen both these sets of drawings (the former set was sold at the Crewe sale in 1903; both are now in America) and though some judges have thought differently, the engravings represent, to my mind, the finest and completest forms of the designs. They seem to me throughout to be superior to the drawings.

There exists, indeed, one painting which is a modification of the sixth plate of the engravings and which is certainly superior to the print; but this painting, which is in tempera on panel, must surely have been of later date than the engraving. It belonged to Sir Charles Dilke and is now in the Tate Gallery (Plate 95).

Here the shape of the design is altered: Satan has wide, out-spread wings, and the sullen sunset splendour of the colouring seems to be in its original condition.

A single plate, of excessive rarity, deserves a mention here. This is the stipple-engraving Mirth (Plate 86).

It reproduces one of the illustrations to “L’ Allegro,” which I remember being charmed by at the sale of the Crewe collection, and which are now in America. Blake was a skilful stipple-engraver after other artists, but after engraving the Mirth by this method he seems to have disliked the effect and re-worked the plate with impetuous strokes of the graver. I only know this state of the print by the reproduction in Mr. Russell’s Catalogue. The stipple-print is in the Print Room of the British Museum; it was acquired at the Linnell sale.

Blake’s last engravings are the seven illustrations to Dante. These are inferior to the Job plates both as designs and as prints; he does not seem to have adapted himself to the larger scale. The two reproduced (Plates 98and 99)

are from a set of early states of the plates, in Mrs. Morse’s collection. These states have not hitherto been described, and may be unique.

are from a set of early states of the plates, in Mrs. Morse’s collection. These states have not hitherto been described, and may be unique.

If the Job is Blake’s grandest work in engraving, showing his powers of imagination at their fullest reach, the little set of woodcuts to Virgil’s “Eclogues” hold us equally, in their idyllic vein, by the charm of complete felicity.

As originally published, they could hardly have had worse chance of recognition and appreciation. They were ill printed, huddled together, four on a page, with grotesquely incongruous surroundings, and mutilated by other hands.

The book in which they appeared was the third edition of Dr. R. J. Thornton’s “Eclogues of Virgil,” in two volumes, with 230 illustrations: it was designed to make the study of Latin easy for beginners, and imitations of the Eclogues by English poets were printed opposite the Latin text. It was published in 1821.

Blake made eighteen drawings in pencil and sepia to illustrate Ambrose Phillips’ imitation of the First Eclogue. These were in the Linnell collection; they are now in America. One subject was not engraved; and of the rest three were engraved by other hands, the result being no longer recognizable as Blake’s work. The frontispiece is on a rather larger scale. Dr. Thornton printed under it an apology for the woodcuts, as showing “less art than genius.”

It was only the persuasion of artists like Lawrence and James Ward which induced him to admit Blake’s work at all. At this time the school of wood-engraving started by Bewick was already infected with the ambition to rival the fine finish of the steel-engravers. Manipulative skill was the quality sought and esteemed. Blake’s bold, swift way with the wood produced work which seemed rude and childish to the trained professionals of Bewick’s school who were also employed on the book, and they exclaimed against it. As Gilchrist records, the blocks were cut down to fit the page. How much the blocks suffered from this mutilation we can now judge; for Linnell preserved two or three sets of proofs from eight of the blocks in their original state. In 1920 one of these sets was presented to the Print Room of the British Museum by Mr. Herbert Linnell; and in the Burlington Magazine (Dec., 1920) I was able to reproduce these eight prints side by side with the same prints as they appeared in Thornton’s book.

Not only were the blocks cut down, but they were worked on by other hands in an effort to make them more presentable. Plates 83 and 84 give the eight woodcuts in their earlier state.

We can only sigh that proofs of the rest of the set were not preserved.

Blake made eighteen drawings in pencil and sepia to illustrate Ambrose Phillips’ imitation of the First Eclogue. These were in the Linnell collection; they are now in America. One subject was not engraved; and of the rest three were engraved by other hands, the result being no longer recognizable as Blake’s work. The frontispiece is on a rather larger scale. Dr. Thornton printed under it an apology for the woodcuts, as showing “less art than genius.”

Not only were the blocks cut down, but they were worked on by other hands in an effort to make them more presentable. Plates 83 and 84 give the eight woodcuts in their earlier state.

We can only sigh that proofs of the rest of the set were not preserved.

Blake had before this made a few “woodcuts on pewter,” notably the head and tail-piece to a ballad of Hayley’s, “Little Tom the Sailor” (and some pages of “Jerusalem” may have been produced by this process).

Now at the age of sixty-three he attacked the wood with the graver for the first time. In spite of his denunciations of the “demons” of chiaroscuro, he did not engrave in outline, like the men who worked after Diirer, but used the “white-line,” long ago employed by Scolari and some other Italians, and made popular in his own time by Bewick. He evoked his forms from the black background with rich gleams and a shadowy suggestiveness. Nowhere else has he treated landscape motives with such interest and enjoyment. These little cuts were the starting-point and inspiration for the pastorals of Calvert and Samuel Palmer.

VII.

Edward Calvert, who under Blake’s inspiration was to make some of the most exquisite small engravings ever done in England, served in the Navy as a midshipman; then determined to forsake the sea and follow art. He came up to London from Devon and sought out a stockbroker, Mr. John Giles, on business of property; and the conversation having diverged to “the grandeur of the ancients,” Mr. Giles went on to tell him of “the divine Blake, who has seen God, sir, and talked with angels.”

I always think that Mr. Butts, who for so many years was the external support of Blake’s imaginative life, commissioning from him a long series of paintings and drawings, must have been of a kindred nature with this delightful, improbable, but quite real stock-broker, John Giles. With their homely English names, and, as one conceives, their innate and innocent reverence for the man of genius, they remind one of those sympathetic natures, all delicacy and sensitiveness within, which Mr. Conrad has discerned and revealed sometimes under the plain, ruddy exterior of an English sea-captain. And I think it an honour to our race that it produces such natures, little versed in terms of art, perhaps, but in such a man as Thomas Butts appearing as a patron how precious to discover, when we remember the pomp and vanity of the great patrons of art, the Popes and potentates, who thwarted and wasted even while they encouraged the genius of men like Michelangelo.

The Butts collection contained much of Blake’s finest work, both in tempera and in water-colour.

Of Blake’s pictures it is difficult to speak, since few of them probably retain their original appearance, and some are darkened wrecks. We learn from the Descriptive Catalogue that he painted at one time in oils; then made a number of what he called “experiment pictures,” of which he says that they were “bruised and knocked about without mercy, to try all experiments.”

In the end he satisfied himself with a kind of tempera painting, using glue instead of the egg medium, on gesso over canvas, panel, copper, or steel. This he absurdly called “fresco,” and asserted that the pictures done in this medium “are known to be unchangeable.”

I knew the Nelson guiding Leviathan (Plate 52) when it was in the possession of the late Mr. T. W. Jackson, of Oxford. It was so dim and darkened that the forms were hardly distinguishable: but before he left it to the nation Mr. Jackson had it restored (in no way repainted) by Mr. Littlejohn, the chief mounter at the Print Room, who had a genius for such work, and whose untimely death in action in the war was a national loss. As it appears now at the Tate Gallery, it makes Blake’s assertion that “clearness and precision have been the chief objects in painting these pictures” seem less preposterous than it does when contemplating the Pitt or The Bard.

I knew the Nelson guiding Leviathan (Plate 52) when it was in the possession of the late Mr. T. W. Jackson, of Oxford. It was so dim and darkened that the forms were hardly distinguishable: but before he left it to the nation Mr. Jackson had it restored (in no way repainted) by Mr. Littlejohn, the chief mounter at the Print Room, who had a genius for such work, and whose untimely death in action in the war was a national loss. As it appears now at the Tate Gallery, it makes Blake’s assertion that “clearness and precision have been the chief objects in painting these pictures” seem less preposterous than it does when contemplating the Pitt or The Bard.

Mr. Sturge Moore thinks these two Blake’s finest “frescoes.” The Bard makes one think that the kind of use of tempera which we see in Tintoretto’s big pictures in the School of San Rocco was what Blake was groping after.

One of the most important of the “frescoes,” The Ancient Britons, described as having figures near life-size, seems to have entirely disappeared. I confess I cannot share Blake’s own great admiration for his Canterbury Pilgrims: it does not seem to me the type of work in which his real genius was engaged.

Nine of the tempera pictures are reproduced in this volume, among them the Nativity (Plate 14),

a strange and exquisite invention, in which the essence of Blake’s spiritual imagination is disclosed. Very beautiful also is the Flight into Egypt (Plate 13).

In quite another vein the Satan smiting Job (Plate 95), with its splendour of symbolic colour, is unusually well preserved and must rank high among Blake’s works.

a strange and exquisite invention, in which the essence of Blake’s spiritual imagination is disclosed. Very beautiful also is the Flight into Egypt (Plate 13).

In quite another vein the Satan smiting Job (Plate 95), with its splendour of symbolic colour, is unusually well preserved and must rank high among Blake’s works.

But most of Blake’s work as a painter is in water-colour. The early English school of water-colour is usually thought of as a school of landscape only. But in the last quarter of the eighteenth century the medium was pretty frequently used for figure-design. Besides Blake, there was Rowlandson, who with reed-pen and wash composed with such inexhaustible fertility scenes from the life around him, which, even when the matter is gross or brutal, are touched with so lively a grace and composed with so abounding a power and ease that we are enchanted. Rowlandson and Mortimer, both gay and liberal livers, were the rival champions of the Academy schools in their youth, and the idols of the students; the tradition of their exuberant promise and facility still lingered when Blake, at twenty-one, entered the schools in 1778.

Mortimer, now almost forgotten, was immensely admired in his day. Blake’s early essays in “history” were modelled on his style. One of these, The Penance of Jane Shore (Plate 1),

was included by Blake in the exhibition of his works in 1809. He covered it with varnish, as a substitute for glass, as Gainsborough did some of his drawings: and the mellow tone it has acquired is very pleasing. The usual practice of painters in water-colour till about the beginning of the nineteenth century was, of course, to wash in the design with Indian-ink, and put the colours on over this grey foundation. This was parallel to the practice of oil-painters who laid in their design in white and brown or grey before they proceeded to colour. The intention was to secure coherence and due subordination of the parts to the whole.

was included by Blake in the exhibition of his works in 1809. He covered it with varnish, as a substitute for glass, as Gainsborough did some of his drawings: and the mellow tone it has acquired is very pleasing. The usual practice of painters in water-colour till about the beginning of the nineteenth century was, of course, to wash in the design with Indian-ink, and put the colours on over this grey foundation. This was parallel to the practice of oil-painters who laid in their design in white and brown or grey before they proceeded to colour. The intention was to secure coherence and due subordination of the parts to the whole.

Some of Blake’s finest drawings have very little colour. And he used the Indian-ink alone with beautiful effect; in no drawing with more felicity than in the Har and Heva in Mr. Marsh’s collection (Plate 4), which has a strange marmoreal quality.

This drawing is one of a set of designs for “Tiriel,” probably the earliest of the Prophetic Books. The whole set of twelve are described by W. M. Rossetti in Gilchrist’s “Life.” But they are now dispersed, and the whereabouts of most of them is unknown. One, however, reproduced in this volume (Plate 5) came into the British Museum in 1913: it was in an extra-illustrated set of Academy Catalogues, with many other interesting drawings by English artists. The figured dress on one of the women is unlike Blake’s mature manner, which disdains pattern: but at this time he was fond of such enlivening ornament.

The little drawing Youth learning from Age (Plate 3), which is brightly tinted, must belong to this period; as also, I think, an early version of Elijah in the Chariot of Fire, which belongs to Mrs. Morse.

The most impressive drawing of this early period is The Breach in a City (Plate 2), of 1784, the first work in which Blake’s powers of grim imagination are displayed in a personal style. This is very slightly coloured.

Blake’s difficulty with water-colour on a large scale was the difficulty of preventing his broad washes from appearing weak and empty in a strong design. To add pattern to dresses was, after his youthful period, uncongenial to him; the accidents of light on varying textures had no interest for him. Arrangements of drapery again were obstacles to that unimpeded movement in which he inveterately delighted. How then was he to give richness and body to his surfaces?

This drawing is one of a set of designs for “Tiriel,” probably the earliest of the Prophetic Books. The whole set of twelve are described by W. M. Rossetti in Gilchrist’s “Life.” But they are now dispersed, and the whereabouts of most of them is unknown. One, however, reproduced in this volume (Plate 5) came into the British Museum in 1913: it was in an extra-illustrated set of Academy Catalogues, with many other interesting drawings by English artists. The figured dress on one of the women is unlike Blake’s mature manner, which disdains pattern: but at this time he was fond of such enlivening ornament.

The little drawing Youth learning from Age (Plate 3), which is brightly tinted, must belong to this period; as also, I think, an early version of Elijah in the Chariot of Fire, which belongs to Mrs. Morse.

The most impressive drawing of this early period is The Breach in a City (Plate 2), of 1784, the first work in which Blake’s powers of grim imagination are displayed in a personal style. This is very slightly coloured.

Blake’s difficulty with water-colour on a large scale was the difficulty of preventing his broad washes from appearing weak and empty in a strong design. To add pattern to dresses was, after his youthful period, uncongenial to him; the accidents of light on varying textures had no interest for him. Arrangements of drapery again were obstacles to that unimpeded movement in which he inveterately delighted. How then was he to give richness and body to his surfaces?

He invented a method, half-painting and half-printing, which yielded, in some sort, the effect he desired. I imagine the method was prompted by the effects of colour-printing obtained from the relief-etchings of the “Songs of Innocence” and the other illuminated books. A similar method had been employed by G. B. Castiglione (1616-1670), and other artists, but doubtless their “monotypes” were unknown to Blake, who achieved besides a much more elaborate effect. The method was to make the design roughly and swiftly on mill-board in distemper (not oil-colours) and while it was wet take an impression from it on paper. The blotted ground-work of this impression was coloured up by hand. The design could be revived on the mill-board when another impression was wanted. Some of Blake’s finest works were produced by this means; for instance, the Elijah

and the Pity.

Most of these works were produced in or about the year 1795, a time of splendid productiveness in Blake’s life. Later, he reverted to transparent water-colour: and in this medium he made hundreds of drawings, the best of which he repeated more than once, with more or less variation in technique as well as design: sometimes using a light tint over the foundation of Indian-ink, and then repeating the design in fuller, richer tones. Thus the set of designs for “Paradise Lost,” reproduced in colour in the Liverpool edition of the poem (1906) are in pale subdued tints, like the Satan watching the endearments of Adam and Eve (Plate 70), which is a version of one of the subjects of the series.

But another version of the whole set is in the Boston Museum, much stronger in colour; I remember particularly the Creation of Eve (Plate 80) with its deep blue sky. Yet other modified versions exist of these Milton illustrations: some were in the Linnell collection.

Among the mass of Blake’s water-colours, whether colour-printed or not, preferences will be various: but a certain number stand out among the rest. The Elohim creating Adam (Plate 37), tremendous in imaginative energy;

But another version of the whole set is in the Boston Museum, much stronger in colour; I remember particularly the Creation of Eve (Plate 80) with its deep blue sky. Yet other modified versions exist of these Milton illustrations: some were in the Linnell collection.

Among the mass of Blake’s water-colours, whether colour-printed or not, preferences will be various: but a certain number stand out among the rest. The Elohim creating Adam (Plate 37), tremendous in imaginative energy;

the Elijah (Plate 42), grand in colour as in design;

the Pity (Plate 36), magnificent in movement and supremely original;

the Wise and Foolish Virgins (Plate 85), one of Blake’s most perfect creations, with its fine pictorial contrast between the calm, ranked movement of the Wise and the tossed and troubled forms of the Foolish, and, above all, the superb dawn landscape and angel blowing his trumpet in the sky;

the Entombment (Plate 45), with its profound and veiled emotion;

the Angel rolling away the stone from the Sepulchre (Plate 78), unusually complete and superbly conceived;

the River of Life (Plate 66), most lovely of Blake’s drawings in its aerial colour;

the Job confessing his Presumption (Plate 43);

the Crucifixion (Plate 44), a grand pictorial invention, though the dicing soldiers in the foreground are not quite worthy of the rest;

each of these (to name no more) is in its different way a passionate design, throbbing with interior life. These alone would suffice for a noble fame.

the Pity (Plate 36), magnificent in movement and supremely original;

the Wise and Foolish Virgins (Plate 85), one of Blake’s most perfect creations, with its fine pictorial contrast between the calm, ranked movement of the Wise and the tossed and troubled forms of the Foolish, and, above all, the superb dawn landscape and angel blowing his trumpet in the sky;

the Entombment (Plate 45), with its profound and veiled emotion;

the Angel rolling away the stone from the Sepulchre (Plate 78), unusually complete and superbly conceived;

the River of Life (Plate 66), most lovely of Blake’s drawings in its aerial colour;

the Job confessing his Presumption (Plate 43);

the Crucifixion (Plate 44), a grand pictorial invention, though the dicing soldiers in the foreground are not quite worthy of the rest;

each of these (to name no more) is in its different way a passionate design, throbbing with interior life. These alone would suffice for a noble fame.

Blake deplored that his best drawings could not have been painted on a large scale as altar-pieces for churches, “to make England, like Italy, respected by respectable men of other countries on account of Art.” Certain it is that the comparative smallness of the scale, and the character of the medium, have impeded recognition of the rare and great qualities of these works.

VIII.

Only in the present year were Blake’s illustrations to Gray’s poems given to the world, in a magnificent volume of full-sized reproductions. They are presumed to have been in Beckford’s collection, which pusst-d into that of the Duke of Hamilton, but were lost or mislaid till 1919, and were only known to Gilchrist by hearsay.

In style the drawings remind us of the “Night Thoughts” series, and one would be inclined to place them rather earlier than 1800, the date presumed by Professor Grierson, their editor, on the strength of a poem written/in the original volume and dedicating them to Mrs. Flaxman. The poem seems to refer to Flaxman’s good offices in transplanting Blake from London to Felpham. But there is no reason why the drawings should not have been made earlier; indeed it seems likelier that Blake offered them, as work he had by him, than that they should have been made for the purpose of presentation.

However, this is a small matter. The drawings are not of Blake’s best work, being hasty in execution, but some of them show him in a vein of humorous fancy, not betrayed elsewhere; others contain the germ of grand designs, and they are of extreme interest as showing the contact of two minds so different as Gray’s and Blake’s. Mr. Grierson, in the admirable essay prefixed to the reproductions, illuminates the subject by reminding us of Johnson’s attitude to Gray: just what Johnson condemned as obsolete mythology is just what sets Blake on fire. We cannot doubt that Gray appeared to Blake as a great Romantic, and hard as it is for us to think ourselves back to the time when Coleridge and Keats and all the Romantic Movement were yet to come, we see how natural it was for Gray’s genius, especially in poems like “The Bard,” to appeal to Blake, who read into the older poet’s verse an imaginative passion that was latent or half-suppressed in the lines he illustrated.

Blake’s last work was the designs for Dante. Would that he had known him earlier! The drawings, a hundred in number, are very unequal. A few are elaborately coloured and completed; many are mere sketches. They also differ greatly in quality. The set were sold in one lot at the Linnell sale. American competition was keen; and during the war the national museums were deprived of their annual purchase grants. Still, by concerted action, sufficient money was raised, and the drawings were saved for the country, or at least for the Empire, since the largest proportion went to the Melbourne Gallery, which contributed the most to the purchase.

https://www.ngv.vic.gov.au/collection/international/print/b/blake/dante.html

https://www.ngv.vic.gov.au/collection/international/print/b/blake/dante.html

Dante ought to have been congenial to Blake, who f said “you have only to work up imagination to the state of vision, and the thing is done”; for of all poets Dante is the one whose imagination is always at the pitch of vision. Blake also, deriding Reynolds’ doctrine of generalized form, insisted much on particularity; and no poet sees with such intense particularity as Dante. But when we look at Blake’s own work, we see forms determinate indeed in outline but generalized in conception; there is no intensity of detail.

The “Commedia” is full of minute and scrupulous observation: Blake never seems to have observed anything for its own sake. Herbert Home in his book on Botticelli, that fine monument of English scholarship, points out that one reason why Dante’s poem is called a Comedy is that it was written in a style that eschewed the exalted tone of Tragedy, disdaining neither the phrase of common speech nor the most familiar images of daily life. Instead of seeking to create an atmosphere of remoteness and grandeur, Dante wants to make his reader see every detail of his visionary journey, and no comparison is thought too homely or undignified if it makes these near and vivid. It is so that Botticelli in the famous series of pen-drawings, now at Berlin, conceives his illustrations; at least he does not conceive them in the manner which we associate with Michelangelo and the tradition derived from his example, a manner disdainful of detail and relieving heroic or grandiose forms against a spectral or murky void.

Blake, before he came to read Dante, was steeped in Milton and the Old Testament, in a world of imagination to which Michelangelesque forms and a vast, vague background were congenial. Even the figures of Dante and Virgil were seen by him in the generalized aspect which he gave to figures from the Bible story. And yet in spite of what appear to be so serious disqualifications, Blake goes to the core of Dante’s matter; for he is akin to the great Italian, if not at all in his mode of vision, in the spiritual intensity of his nature. He is not so human as Dante in the passionate feeling of the heart; but spiritual anguish, spiritual ecstasy, he expresses with a power that could hardly be surpassed. Botticelli is his only rival. Both these artists possessed a faculty, unrivalled, I think, by any other European artist, of creating forms that float or rush upon the air, so that we seem to share the lightness of their buoyancy and the motion of their flight. Botticelli has all the advantage of a Florentine, versed in Dante’s poetry from his youth, and living in one of the greatest times of art: yet there are moments in which Blake, by his intense passion, excels him. Botticelli gives us little of the terribleness of the poet: his pen-work, with its fluent outline, can render nothing of the atmosphere, the changing glooms and irradiations which mean so much in Dante; he hardly begins to persuade us that he is really living in his imagination till we come to the “Purgatory” and the “Paradise,” where he moves as in native air and creates pages of enchanting beauty. Blake, with all his frequent failures for rarely is a single design quite satisfying as a whole contrives, with his strange elemental power, to give life to the strangest of the creatures he imagines.

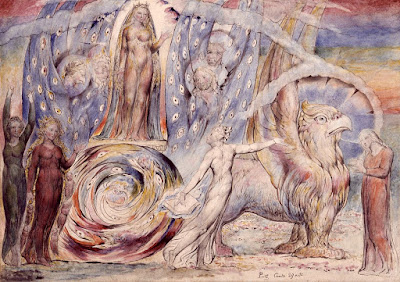

Perhaps, of all the series, the scene in the “Earthly Paradise,” with the mystical procession, and the stream dividing Dante from Matilda as it winds through the flowery meadow, and the flames of the seven candles reflected in the water (Plate 103) is the most felicitous.

Here Blake’s peculiar rainbow tints give just the sensation of unearthly radiance that we require. And the unfinished character of the drawing seems, paradoxically, to make it more complete to our imaginations It is the same with another lovely sketch, washed with colour, of the Angel departing in his boat “without sail or oar,” which is also in the British Museum (Plate 101).

Of the elaborated and fully-coloured designs none surpasses the Paolo and Francesca, with its great swirl of anguished lovers borne upon the wind, which is now at Birmingham: it is one of those which Blake engraved (Plate 98

A very beautiful design for the “Purgatory” is at Oxford. And Blake seems to have been especially fortunate in those scenes where the poets climb the mount of Purgatory, with the sea, dark and glittering, below them: two or three of these are in the Tate Gallery, with some impressive pages from the “Inferno.” One of the finest of the full-coloured designs is the Lucia carrying Dante in his sleep (Plate 100), with its wonderful sky of stars.

IX.

“The painters of England are unemployed in public works.” Blake’s lament and desire show how he conceived of the function and need of art in national life. Isolated in his own age, he was ever conscious of the lost medieval tradition and striving to take up again its broken threads. His own art may be charged with eccentricity, partly due to an abnormal nature, partly to want of education and the warping circumstances of his time; but he aspired to belong to the central tradition. And we may with more justice perhaps charge with “eccentricity” the trend of nineteenth-century art, embogged in a naturalism which may well appear to future times as little significant as the “naturalist” movement in seventeenth-century Italy.

Blake’s immediate influence on his little group of young disciples was mainly through the pastoral vein of his woodcuts, and did not succeed in stimulating them to arduous creation. The torpor of prosperous commercialism came on England, and was heavy to contend against. When Rossetti sought for a tradition to sustain the effort of the Pre-Raphaelites to reconnect the arts and the imaginative life, he too looked back to the Middle Ages; and on the path behind there was no one but Blake to help him. Sterile dogmas have done their best to drain the arts of imagination: but no fulness of power will be theirs till the imaginative life pours into them again. Of that time Blake is the herald and the prophet.

LAURENCE BINYON.

Wikipedia biography of william Blake

Wikipedia biography of Laurence binyon ...

https://ebooks.adelaide.edu.au/b/blake/william/drawings-and-engravings/introduction.html

E-book binyon's List Of illustrations ...

https://ebooks.adelaide.edu.au/b/blake/william/drawings-and-engravings/contents.html

Online Brittanica ...

https://www.britannica.com/biography/William-Blake#ref931517

Paradise Lost

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Paradise_Lost

Paradise Regained...

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Paradise_Regained