... of the seven deadly sins, the eighth and most horrid is emotional blackmail ... whilst for this blogger, the only sacred thing is life itself

Wednesday, June 12, 2019

emma kunz

https://www.emma-kunz.com/en/

https://www.apollo-magazine.com/emma-kunz-drawings-serpentine/

https://flashbak.com/emma-kunz-the-divine-pendulum-drawings-415908/

Saturday, June 8, 2019

Friday, June 7, 2019

Mnemosyne ... Goddess of Memory and Mother of the Nine Muses ... Aby Warburg's Mnemosyne Atlas ... Sylvia Kantaris' iconoclastic poem ...

Mnemosyne was one of the Titans, daughter of Uranus and Gaea, and goddess of memory. She was also occassionally referred to as Mneme; however, this was the name of another goddess. She was the oracular goddess of the underground oracle of Trophonios in the region of Boeotia.

Zeus slept with Mnemosyne for nine consecutive days, eventually leading to the birth of the nine Muses. In Hesiod's Theogony, the kings and poets were inspired by Mnemosyne and the Muses, thus getting their extraordinary abilities in speech and using powerful words.

The name Mnemosyne was also used for a river in the Underworld, Hades, which flowed parallel to the river of Lethe (which means forgetfulness). Usually, the souls of the dead would drink water from Lethe, so that they would forget their past lives when they would be reincarnated. However, the souls of the novices were told to drink water from Mnemosyne. This myth may have been part of a small mystic religion or be tied to Orphic poetry.

Artists portray Mnemosyne but rarely seem to convey her character or attributes in a convincing way, failing to re-create the "person" as far as i can see ... some just use her name as a kind of coathanger for their own fantasy, which is perfectly legitimate ... but this is why she no longer inhabits the modern imagination

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mnemosyne

https://warburg.library.cornell.edu/about/aby-warburg

https://zkm.de/en/event/2016/09/aby-warburg-mnemosyne-bilderatlas

https://zkm.de/en/publication/aby-warburg-mnemosyne-bilderatlas-english

https://owlcation.com/humanities/The-Muses-The-Nine-Muses-Goddesses-of-Greek-Mythology

i first came across her name in this poem by the sweet sylvia kantaris ...

The Tenth Muse

My muse is not one of the nine nubile

daughters of Mnemosyne

in diaphanous nightshifts

with names that linger in the air

like scent of jasmine or magnolia

on Mediterranean nights.

Nor was any supple son of Zeus appointed

to pollinate my ear with poppy dust

or whispers of sea-spray.

My muse lands with a thud

like a sack of potatoes.

He has no aura.

The things he grunts are things

I’d rather not hear.

His attitude is ‘Take it or leave it, that’s

the way it is’, drumming his fingers

on an empty pan by way of music.

If I were a man I would enjoy

such grace and favour,

tuning my fork to Terpsichore’s lyre,

instead of having to cope with this dense

late-invented eunuch

with no more pedigree than the Incredible Hulk,

who can’t play a note

and keeps repeating ‘Women

haven’t got the knack’

in my most delicately strung and scented ear.

daughters of Mnemosyne

in diaphanous nightshifts

with names that linger in the air

like scent of jasmine or magnolia

on Mediterranean nights.

Nor was any supple son of Zeus appointed

to pollinate my ear with poppy dust

or whispers of sea-spray.

My muse lands with a thud

like a sack of potatoes.

He has no aura.

The things he grunts are things

I’d rather not hear.

His attitude is ‘Take it or leave it, that’s

the way it is’, drumming his fingers

on an empty pan by way of music.

If I were a man I would enjoy

such grace and favour,

tuning my fork to Terpsichore’s lyre,

instead of having to cope with this dense

late-invented eunuch

with no more pedigree than the Incredible Hulk,

who can’t play a note

and keeps repeating ‘Women

haven’t got the knack’

in my most delicately strung and scented ear.

in japan's modern culture of assimilating and then transforming european myth, we get this gothic sadistic creation ...

i don't know if the surrealists identified her as their own in a deliberate way although surely paul delvaux, giorgio di chirico, and remedios varo, must have stopped to think about her attributes

the lamp ?

the wax tablet ?

moonlight ?

someone else points up the relationship between memory and architecture ... https://newprairiepress.org/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?referer=https://www.google.com/&httpsredir=1&article=1190&context=oz

mnemosyne and lethe were also mythical rivers, drink from one for remembering, or from the other for forgetting

michael ayrton ... text copied from a history of the ray-jones family ... and a few images from his prodigiously fertile imagination ...

Michael Ayrton

b: 20 FEB 1921

d: 17 NOV 1975

From "Hertha Ayrton: A Memoir" by Evelyn Sharp, publ Edward Arnold, London, 1926:

p.297: But the grandchild who absorbed her affectionate interest more than any other was Barbie's child Michael..... On him she lavished unlimited tenderness, and the greater portion of her leisure, all through the last two years of her life. Every day he came round to Norfoldk Square in his perambulator, and any visitor who dropped in about tea-time would find them together in the drawing-room, she singing her old French songs, and sometimes old English folk nursery rhymes, as she used to sing to her own little daughter. It was very pretty to see them together and to hear the baby voice echoing the refrain. Once, when the visitor happened to be the doctor, Michael greeted him gravely with: "An apple a day keeps the doctor away"

From the Dictionary of National Biography 1971-1980:

AYRTON, MICHAEL (1921-1975), artist and writer, was born in London 20 February 1921, the only child of Gerald Gould, poet and journalist, of 3 Hamilton Terrace, London, and his wife, Barbara Ayrton, sometime chairman of the Labour Party, and whose surname Ayrton adopted on becoming a practising artist. Michael Ayrton left a co-educational school early. He studied painting in Vienna and Paris, working briefly under Pavel Tchelitchew, and attended Heatherley's Art School and various other art schools in London.

He travelled to Spain, saw some of the siege of Barcelona during the Spanish civil war, and spent the summer of 1939 with fellow painters and friends F John Minton (qv) and Michael Middleton at Les Baux in France. After the outbreak of war, Ayrton returned to London, had his first exhibition at the Zwemmer Gallery, and with John Minton, during leave from the RAF, executed the designs for (Sir) John Gielgud's Macbeth, staged in 1942. Ayrton was invalided out of the RAF in 1942 and shared an exhibition with Minton at the Leicester Galleries. From that time his life was marred by ill health, borne with much stoical courage, and his career as an artist developed from a precocity noted by such distinguished elders as P Wyndham Lewis (qv) (for whom Ayrton acted for some time as visual amanuensis) to a versatile fruition which never brought the honours, the critical acclaim, or the financial success enjoyed by many of his contemporaries.

In this respect, in a country and society which still regards amateurism as a professional advantage, Ayrton suffered from his relentless curiosity, his considerable eclecticism, and his formidable erudition, backed by a strong physical presence which many persons of weaker intellect or personality found intimidating. In fact his handsome head, with long. straight, swept-back hair and full beard, the powerful torso of the sculptor, and the mellifluous voice of a born teacher and conversationalist were compellingly attractive. What left him, at the height of his career, with a single honour, a doctorate from Exeter University (1975), and no official recognition from the British 'art establishment' was the view, commonly held, that his exceptionally varied output was the sign of a jack of all trades.

For more than three decades he practised as painter, sculptor, draughtsman, engraver, portraitist, stage-designer, book illustrator, novelist, short story writer, essayist, critic, art historian, radio and television broadcaster, and cinema and television film-maker. While inevitably in an oeuvre so prodigious he occasionally let slip work that was not of the first rank, there was in fact none of the trades listed above of which he was not the master.

Ayrton's principal exhibitions, other than regular dealers' selling shows in Britain, Europe, the USA, and Canada, were: Wakefield City Art Gallery (and subsequently on tour) in 1949; a retrospective at the Whitechapel Art Gallery in London in 1955; the Philadelphia Museum of Art in 1963; the National Gallery of Canada (a regional tour) in 1965; Reading City Art Gallery in 1969; the Bruton Gallery, Somerset in 1971; the University of Sussex in 1972; Portsmouth City Art Gallery (and subsequently on tour) in 1973; the University of Pennsylvania in 1973.

His most important exhibitions, however, were 'Word and Image' - a remarkably inventive show devoted to a comparison of the work of Ayrton and Wyndham Lewis showing the inter-relationship, not only of the two artists and their styles, but also of their writings as well as their visual work. This was held in 1971 at the National Book League, London. The major retrospective exhibition which Ayrton should have had in his lifetime only occurred posthumously in 1977 at the Birmingham City Museums and Art Gallery and subsequently on tour; in 1981 there was a substantial touring exhibition at the Bruton Gallery in Somerset, the National Museum of Wales etc.

Ayrton's visual work, apart from his portraits, tended to be thematic, with certain ideas and images either obsessively recorded or constantly recurring. The discovery of Greek landscape and mythology was to haunt his work till he died. (He travelled extensively in Greece and the Hellenistic world.) Daedelus and Icarus, Talos, and above all the Minotaur inspired much of his finest work, ranging from pencil sketches to huge bronzes. For a benevolently eccentric American millionaire, Armand Erpf, he created in 1968 at Arkville in New York State a gigantic maze built of brick and stone, with a seven-foot bronze Minotaur and a seven-foot bronze of Daedelus and Icarus in two central chambers.

Flight was a permanent obsession. Hector Berlioz preoccupied him for years and inspired sculptures, paintings, a memorable short story and a remarkable BBC television programme which he devised and narrated. Mirrors fascinated him and, with their infinite variety of and capacity for reflections, dominated his later sculptures where he mingled bronze, polished metal sheet, and perspex to extraordinary effects. For the two years before his death he had been working on a major BBC television series on the multiple possibilities of mirrors and their imagery in life, art, mathematics, philosophy, and astronomy.

Ayrton's literary output was as varied as his visual work. He was a fine critic (he was art critic of the Spectator from 1944 to 1946) and in these fields ranged from books on British Drawings in 1946 and Hogarth's Drawings (1948) via several collections of distinguished essays, notably Golden Sections (1957) and The Rudiments of Paradise (1971), to a pioneering scholarly monograph Giovanni Pisano, Sculptor (1969), which had an introduction by Henry Moore.

As a poet he showed notable talent in the fragmentary The Testament of Daedalus (1962) (a foretaste and forerunner of his subsequent novel, The Maze Maker, 1967) and he published posthumously in 1977 Archilochos, a translation (with the assistance of Professor G S Kirk) of the seventh-century Greek poet who wrote in the Parian script. This book, containing Ayrton's last published words, was illustrated by his own characteristically spiky etchings, done in the last eighteenth months of his life.

Ayrton produced one collection of short stories, Fabrications (1972), influenced by Borges, in the tricks they played with time, history and memory, but entirely Ayrtonian in their dry wit, originality of imagination, and a wholly beneficent solipsism deriving not from personal vanity but from the indubitable fact that his own experiences, serendipties, and ideas were genuinely of greater creative interest to himself and others than the notions and characters of most other people, Giovanni Pisano and Hector Berlioz excepted.

His two novels, The Maze Maker and The Midas Consequence (1974) were both an integral part of Ayrton's visual life. The former, a virtuoso account of the lives of Daedalus and Icarus, dealt with mythology, Crete, the Minotaur, the excitement of flight, and above all, the genius of the artist as master craftsman. The Midas Consequence is an equally virtuoso performance, dealing with the joys and the pitfalls of being a prolific, omni-talented and internationally revered modern artist. The hero, Capisco, is obviously - too obviously, for the unwary - based on Picasso. He is, of course, far more than that and he is, in part at least, Michael Ayrton, but ultimately he is the paradigmatic artist and genius, enriched and pampered by society but, in the end, the property and prey of that same society.

Ayrton was a man who travelled widely throughout his life, was blessed by considerable domestic felicity, was a much loved member of the Savile Club, annd had a large number of friends. In 1951 he moved, with his wife, who was a distinguished authority on English cooking, a superb hostess, and a writer herself, to Bradfields, a beautiful sixteenth-century country house in Essex, formerly the property of Sir Francis Meynell (qv). Bradfields was Ayrton's principal home, social centre, and studio until his death.

Ayrton married, in 1951, Elisabeth, daughter of Douglas Walshe, writer, who had three daughters by her first marriage to Nigel Balchin, writer (1908-68). Michael and Elisabeth Ayrton had no children. He died, suddenly, of a heart attack at his London flat, 17 November 1975.

[Peter Canon-Brookes, Michael Ayrton - an illustrated commentary, 1978; T G Rosenthal, 'Michael Ayrton: a Memoir', Encounter, May 1976; private information; personal knowledge.] T G Rosenthal.

From the Daily Telegraph for 18 November 1975:

Michael Ayrton, the artist, who has died, aged 54, had a many-sided talent which brought him recognition in diverse artistic fields. Primarily a painter and sculptor, he was a notable theatrical designer and latterly a prize-winning writer. He was for a time art critic of the Spectator, made documentary films, and sat on the wartime BBC "Brains Trust," its youngest participant. He developed an extraordinary obsession with the Greek myth of Daedalus, which he worked out in paint, drawing, sculpture and verse before publishing in 1967 his tour de force "The Maze Maker" which he later claimed was "dictated" to him by Daedalus. It won the 1968 Heinemann award for literature.

Mr Ayrton was commissioned to design and build the biggest maze in the world and the first to be built in stone and brick since antiquity, in the Catskill Mountains in New York State. The maze, 3,000 feet long, has walls six feet high with earth ramparts.

Suffragette mother:

The son of Gerald Gould, a radical journalist and Georgian poet, and Barbara Ayrton, a suffragette who became chairman of the Labour Party, Michael Ayrton was born Ayrton-Gould but eventually discarded his patrynomic. He trained as an artist in London, Paris and Vienna, having left school at 14 and by 1942, still only 21, was exhibiting at the Leicester Galleries. He soon showed an interest in theatrical decor, working on John Gielgud's 1942 revival of "Macbeth," the Sadler's Wells ballet and the 1946 Covent Garden production of Purcell's "The Fairy Queen." Already he had published a book on British drawings and continued over the years to produce art books. He was a fine book-illustrator whose pictures graced editions of "The Duchess of Malfi," "Three Plays of Euripides" and "The Trial and Execution of Socrates" besides many others.

Retrospective exhibition:

His reputation as a painter continued to grow and in 1952 he turned to sculpture, working in the barn at his Essex home. In 1955, still only 34, he was accorded the retrospective exhibition of his work at the Whitechapel Gallery. In 1957, he gave his first exhibition as a sculptor, including some bronzes eight feet tall. His preoccupation with the Daedalus theme began in 1961 when he presented the story of Icarus in 14 bronzes. His book "The Testament of Daedalus" appeared in 1962. One of his statues of Icarus stands near St Paul's Cathedral in Old Change Court. In 1969 he was commissioned to emulate another of Daedalus's feats and make a golden honeycomb for a New Zealand patron. For some years he had had difficulty in sculpting because of arthritis.

ORIGINAL MIND: Episodic mind

David Holloway writes: Michael Ayrton's writing, other than his straight art criticism, very much reflected his fascination with the Minotaur legend. His most successful novel, "the Maze Maker" (1967) was a cleverly executed fictional autobiography of Daedalus, the legendary builder of Minos's Maze. The style was episodic, and meaning occasionally not easy to find, as with some of Ayrton's sculptures, but the whole was stamped with the writer's extremely original mind. Later work, like "Fabrications" (1972) tended to be even more fragmented, an honest experiment by an artist who did not find words sufficiently pliable for his purposes. His writing and broadcasting about art, by contrast, could be direct and brilliant.

Guardian 18 November 1975

Michael Ayrton

Artist, sculptor, and author Michael Ayrton died yesterday at his London flat. He was 54. Mr Ayrton was also an illustrator and theatre designer and, in the 1940s, became the youngest member of the BBC's radio Brains Trust. He was born in London, the son of poet and critic Gerald Gould. His mother, Barbara Ayrton Gould was a Labour MP and at one time, party chairman. Mr Ayrton, who married in 1951, leaves a wife and three stepdaughters.

T. G. Rosenthal writes: Michael Ayrton was a strangely controversial figure, perhaps because his remarkable versatility gave critics the opportunity to accuse him of that most terrible of English crimes, being "too clever by half." Only 54 and still at the height of his powers, he had progressed from being more or less an infant prodigy to a strange obscurity, where the cultural establishment is aware of the artist's existence but not of his talents. He painted Welsh landscapes with Graham Sutherland, and fell under the spell of the Greek landscape and "above all Greek mythology, which, in a wholly beneficiant sense, obsessed him. His first novel, about Daedelus and Icarus, The Mazemaker, won the William Heinemann award and his second, the Midas Consequence, about an artist of Picasso's Protean energies were but one side of his writing. In Fabrications he was a fabulist like Borges and in his monograph on Giovanni Pisano, an art historian and scholar. In 1976 he will have a major retrospective at the Birmingham City museum and art gallery.

Guardian 12 March 1982: Exeter, John Dalton

Michael Ayrton

A man in his time plays many parts and Michael Ayrton probably played too many for his own good as an artist. He started his career in 1941 as a theatre designer and although he was variously craftsman and book illustrator, painter and sculptor as well as a TV personality, I feel he was better with words than he was with images and objects. He was a brilliant conversationalist, so steeped in art history, so knowledgeable and acutely critical and aware of facts, that his intuitive gifts and imagination as an artist got buried.

Any show of Ayrton's work looks terribly mannered and eclectic. There are whiffs of archaic Greek sculpture, Renaissance painters like Signorelli, pretty obvious borrowings from Blake and Palmer. Yet he is closest of all to Fuseli (dark dramatic wash drawings, sinister subject matter hinting at corruption and nightmare); his Minotaur etchings of 1971 leaning heavily on Picasso; and, among his sculpture, surely there are references in his head of the brooding Berlioz to Guardier-Brzeska, in his acrobats to Reg Butler, in other aggressive pieces to Germaine Richier and Elizabeth Frink, even in heads within heads to the helmets of Henry Moore? This large exhibition reveals him as a tortured soul expressing himself powerfully. Ayrton's work may be seen in most city art galleries here and America yet seeing so many works -- 177 in all -- one realises how haunted he was by Greek myths and dark gods, and how his work seems locked in the past. There is terror and pathos here but little celebration and praise.

Michael Ayrton: Recurring Themes and Images. Exeter Museum until April 3.

Armand Erpf's Maze

From 'Christmas Greetings 2004', a christmas letter from Robert McArthur of Stevenage, whose wife Ibby was the daughter of Dodo, Cecil Gould's sister.

"In September 1967, Armand Erpf, an American millionaire and a financial genius of Czechoslovak origin who had made a fortune on the New York Stock Exchange, met an English scuptor, Michael Ayrton, at a party in New York. Michael already had a considerable reputation as a stage designer, artist and sculptor and had recently completed a novel "The Maze Maker" based on the life of Daedalus. Michael later said "Armand Erpf was a courteous and well spoken elderly gentleman...... I thought 'This man is mad... what does he want?'" He wanted Michael to build a full-size brick maze in the grounds of his estate in the Catskill Mountains in New York State. Michael prepared some preliminary drawings, despatched them, and thought no more of this strange encounter. Some time later, when Michael was preparing to leave California where he had been lecturing at the university, he received a phone call: "This is Armand Erpf. Go ahead!"

And so on a hot June day in 2004, Jo [Robert's daughter] and I drove some 70 miles north west of her home in New Paltz to Arkville, a small town near to the Erpf Educational Foundation where, some time previously, Jo had given a geographical presentation not knowing that, nearby, was the astounding creation of Michael Ayrton, who was, in fact, Ibby's nephew and Jo's first coursin, once removed!

As the structure is in the private grounds of the Erpf estate, we were met by the caretaker, who led us by a curcuitous route through the woods to the maze. The starting point is actrually a twelve-foot circular mosaid made of local tiles. From this, a path of polished stones taken from a nearby brook leads to the entrance, passing throgh Greek columns that Armand Erpf had acquired and Michael used to celebrate the entrance to the maze itself. One thousand, six hundred and eighty feet of narrow pathways, between walls of brick and stone eighteen inches thick and eight feet high, the maze contains 210,000 bricks in an area two hundred feet across. The double centre is based on the form of the Cretan two-headed axe. To either side, the central chambers contain magnificent seven-foot-high bronze statues, one of Daedalus, the maze-maker, and the other the Minotaur, a monster, half-bull, half-man that Theseus slew with the help of Ariadne. And so, standing with Jo in the centre of this unque structure, we remembered Michael, with whom Ibby and her brother John played when they were children."

b: 20 FEB 1921

d: 17 NOV 1975

From "Hertha Ayrton: A Memoir" by Evelyn Sharp, publ Edward Arnold, London, 1926:

p.297: But the grandchild who absorbed her affectionate interest more than any other was Barbie's child Michael..... On him she lavished unlimited tenderness, and the greater portion of her leisure, all through the last two years of her life. Every day he came round to Norfoldk Square in his perambulator, and any visitor who dropped in about tea-time would find them together in the drawing-room, she singing her old French songs, and sometimes old English folk nursery rhymes, as she used to sing to her own little daughter. It was very pretty to see them together and to hear the baby voice echoing the refrain. Once, when the visitor happened to be the doctor, Michael greeted him gravely with: "An apple a day keeps the doctor away"

From the Dictionary of National Biography 1971-1980:

AYRTON, MICHAEL (1921-1975), artist and writer, was born in London 20 February 1921, the only child of Gerald Gould, poet and journalist, of 3 Hamilton Terrace, London, and his wife, Barbara Ayrton, sometime chairman of the Labour Party, and whose surname Ayrton adopted on becoming a practising artist. Michael Ayrton left a co-educational school early. He studied painting in Vienna and Paris, working briefly under Pavel Tchelitchew, and attended Heatherley's Art School and various other art schools in London.

He travelled to Spain, saw some of the siege of Barcelona during the Spanish civil war, and spent the summer of 1939 with fellow painters and friends F John Minton (qv) and Michael Middleton at Les Baux in France. After the outbreak of war, Ayrton returned to London, had his first exhibition at the Zwemmer Gallery, and with John Minton, during leave from the RAF, executed the designs for (Sir) John Gielgud's Macbeth, staged in 1942. Ayrton was invalided out of the RAF in 1942 and shared an exhibition with Minton at the Leicester Galleries. From that time his life was marred by ill health, borne with much stoical courage, and his career as an artist developed from a precocity noted by such distinguished elders as P Wyndham Lewis (qv) (for whom Ayrton acted for some time as visual amanuensis) to a versatile fruition which never brought the honours, the critical acclaim, or the financial success enjoyed by many of his contemporaries.

In this respect, in a country and society which still regards amateurism as a professional advantage, Ayrton suffered from his relentless curiosity, his considerable eclecticism, and his formidable erudition, backed by a strong physical presence which many persons of weaker intellect or personality found intimidating. In fact his handsome head, with long. straight, swept-back hair and full beard, the powerful torso of the sculptor, and the mellifluous voice of a born teacher and conversationalist were compellingly attractive. What left him, at the height of his career, with a single honour, a doctorate from Exeter University (1975), and no official recognition from the British 'art establishment' was the view, commonly held, that his exceptionally varied output was the sign of a jack of all trades.

For more than three decades he practised as painter, sculptor, draughtsman, engraver, portraitist, stage-designer, book illustrator, novelist, short story writer, essayist, critic, art historian, radio and television broadcaster, and cinema and television film-maker. While inevitably in an oeuvre so prodigious he occasionally let slip work that was not of the first rank, there was in fact none of the trades listed above of which he was not the master.

Ayrton's principal exhibitions, other than regular dealers' selling shows in Britain, Europe, the USA, and Canada, were: Wakefield City Art Gallery (and subsequently on tour) in 1949; a retrospective at the Whitechapel Art Gallery in London in 1955; the Philadelphia Museum of Art in 1963; the National Gallery of Canada (a regional tour) in 1965; Reading City Art Gallery in 1969; the Bruton Gallery, Somerset in 1971; the University of Sussex in 1972; Portsmouth City Art Gallery (and subsequently on tour) in 1973; the University of Pennsylvania in 1973.

His most important exhibitions, however, were 'Word and Image' - a remarkably inventive show devoted to a comparison of the work of Ayrton and Wyndham Lewis showing the inter-relationship, not only of the two artists and their styles, but also of their writings as well as their visual work. This was held in 1971 at the National Book League, London. The major retrospective exhibition which Ayrton should have had in his lifetime only occurred posthumously in 1977 at the Birmingham City Museums and Art Gallery and subsequently on tour; in 1981 there was a substantial touring exhibition at the Bruton Gallery in Somerset, the National Museum of Wales etc.

Ayrton's visual work, apart from his portraits, tended to be thematic, with certain ideas and images either obsessively recorded or constantly recurring. The discovery of Greek landscape and mythology was to haunt his work till he died. (He travelled extensively in Greece and the Hellenistic world.) Daedelus and Icarus, Talos, and above all the Minotaur inspired much of his finest work, ranging from pencil sketches to huge bronzes. For a benevolently eccentric American millionaire, Armand Erpf, he created in 1968 at Arkville in New York State a gigantic maze built of brick and stone, with a seven-foot bronze Minotaur and a seven-foot bronze of Daedelus and Icarus in two central chambers.

Flight was a permanent obsession. Hector Berlioz preoccupied him for years and inspired sculptures, paintings, a memorable short story and a remarkable BBC television programme which he devised and narrated. Mirrors fascinated him and, with their infinite variety of and capacity for reflections, dominated his later sculptures where he mingled bronze, polished metal sheet, and perspex to extraordinary effects. For the two years before his death he had been working on a major BBC television series on the multiple possibilities of mirrors and their imagery in life, art, mathematics, philosophy, and astronomy.

Ayrton's literary output was as varied as his visual work. He was a fine critic (he was art critic of the Spectator from 1944 to 1946) and in these fields ranged from books on British Drawings in 1946 and Hogarth's Drawings (1948) via several collections of distinguished essays, notably Golden Sections (1957) and The Rudiments of Paradise (1971), to a pioneering scholarly monograph Giovanni Pisano, Sculptor (1969), which had an introduction by Henry Moore.

As a poet he showed notable talent in the fragmentary The Testament of Daedalus (1962) (a foretaste and forerunner of his subsequent novel, The Maze Maker, 1967) and he published posthumously in 1977 Archilochos, a translation (with the assistance of Professor G S Kirk) of the seventh-century Greek poet who wrote in the Parian script. This book, containing Ayrton's last published words, was illustrated by his own characteristically spiky etchings, done in the last eighteenth months of his life.

Ayrton produced one collection of short stories, Fabrications (1972), influenced by Borges, in the tricks they played with time, history and memory, but entirely Ayrtonian in their dry wit, originality of imagination, and a wholly beneficent solipsism deriving not from personal vanity but from the indubitable fact that his own experiences, serendipties, and ideas were genuinely of greater creative interest to himself and others than the notions and characters of most other people, Giovanni Pisano and Hector Berlioz excepted.

His two novels, The Maze Maker and The Midas Consequence (1974) were both an integral part of Ayrton's visual life. The former, a virtuoso account of the lives of Daedalus and Icarus, dealt with mythology, Crete, the Minotaur, the excitement of flight, and above all, the genius of the artist as master craftsman. The Midas Consequence is an equally virtuoso performance, dealing with the joys and the pitfalls of being a prolific, omni-talented and internationally revered modern artist. The hero, Capisco, is obviously - too obviously, for the unwary - based on Picasso. He is, of course, far more than that and he is, in part at least, Michael Ayrton, but ultimately he is the paradigmatic artist and genius, enriched and pampered by society but, in the end, the property and prey of that same society.

Ayrton was a man who travelled widely throughout his life, was blessed by considerable domestic felicity, was a much loved member of the Savile Club, annd had a large number of friends. In 1951 he moved, with his wife, who was a distinguished authority on English cooking, a superb hostess, and a writer herself, to Bradfields, a beautiful sixteenth-century country house in Essex, formerly the property of Sir Francis Meynell (qv). Bradfields was Ayrton's principal home, social centre, and studio until his death.

Ayrton married, in 1951, Elisabeth, daughter of Douglas Walshe, writer, who had three daughters by her first marriage to Nigel Balchin, writer (1908-68). Michael and Elisabeth Ayrton had no children. He died, suddenly, of a heart attack at his London flat, 17 November 1975.

[Peter Canon-Brookes, Michael Ayrton - an illustrated commentary, 1978; T G Rosenthal, 'Michael Ayrton: a Memoir', Encounter, May 1976; private information; personal knowledge.] T G Rosenthal.

From the Daily Telegraph for 18 November 1975:

Michael Ayrton, the artist, who has died, aged 54, had a many-sided talent which brought him recognition in diverse artistic fields. Primarily a painter and sculptor, he was a notable theatrical designer and latterly a prize-winning writer. He was for a time art critic of the Spectator, made documentary films, and sat on the wartime BBC "Brains Trust," its youngest participant. He developed an extraordinary obsession with the Greek myth of Daedalus, which he worked out in paint, drawing, sculpture and verse before publishing in 1967 his tour de force "The Maze Maker" which he later claimed was "dictated" to him by Daedalus. It won the 1968 Heinemann award for literature.

Mr Ayrton was commissioned to design and build the biggest maze in the world and the first to be built in stone and brick since antiquity, in the Catskill Mountains in New York State. The maze, 3,000 feet long, has walls six feet high with earth ramparts.

Suffragette mother:

The son of Gerald Gould, a radical journalist and Georgian poet, and Barbara Ayrton, a suffragette who became chairman of the Labour Party, Michael Ayrton was born Ayrton-Gould but eventually discarded his patrynomic. He trained as an artist in London, Paris and Vienna, having left school at 14 and by 1942, still only 21, was exhibiting at the Leicester Galleries. He soon showed an interest in theatrical decor, working on John Gielgud's 1942 revival of "Macbeth," the Sadler's Wells ballet and the 1946 Covent Garden production of Purcell's "The Fairy Queen." Already he had published a book on British drawings and continued over the years to produce art books. He was a fine book-illustrator whose pictures graced editions of "The Duchess of Malfi," "Three Plays of Euripides" and "The Trial and Execution of Socrates" besides many others.

Retrospective exhibition:

His reputation as a painter continued to grow and in 1952 he turned to sculpture, working in the barn at his Essex home. In 1955, still only 34, he was accorded the retrospective exhibition of his work at the Whitechapel Gallery. In 1957, he gave his first exhibition as a sculptor, including some bronzes eight feet tall. His preoccupation with the Daedalus theme began in 1961 when he presented the story of Icarus in 14 bronzes. His book "The Testament of Daedalus" appeared in 1962. One of his statues of Icarus stands near St Paul's Cathedral in Old Change Court. In 1969 he was commissioned to emulate another of Daedalus's feats and make a golden honeycomb for a New Zealand patron. For some years he had had difficulty in sculpting because of arthritis.

ORIGINAL MIND: Episodic mind

David Holloway writes: Michael Ayrton's writing, other than his straight art criticism, very much reflected his fascination with the Minotaur legend. His most successful novel, "the Maze Maker" (1967) was a cleverly executed fictional autobiography of Daedalus, the legendary builder of Minos's Maze. The style was episodic, and meaning occasionally not easy to find, as with some of Ayrton's sculptures, but the whole was stamped with the writer's extremely original mind. Later work, like "Fabrications" (1972) tended to be even more fragmented, an honest experiment by an artist who did not find words sufficiently pliable for his purposes. His writing and broadcasting about art, by contrast, could be direct and brilliant.

Guardian 18 November 1975

Michael Ayrton

Artist, sculptor, and author Michael Ayrton died yesterday at his London flat. He was 54. Mr Ayrton was also an illustrator and theatre designer and, in the 1940s, became the youngest member of the BBC's radio Brains Trust. He was born in London, the son of poet and critic Gerald Gould. His mother, Barbara Ayrton Gould was a Labour MP and at one time, party chairman. Mr Ayrton, who married in 1951, leaves a wife and three stepdaughters.

T. G. Rosenthal writes: Michael Ayrton was a strangely controversial figure, perhaps because his remarkable versatility gave critics the opportunity to accuse him of that most terrible of English crimes, being "too clever by half." Only 54 and still at the height of his powers, he had progressed from being more or less an infant prodigy to a strange obscurity, where the cultural establishment is aware of the artist's existence but not of his talents. He painted Welsh landscapes with Graham Sutherland, and fell under the spell of the Greek landscape and "above all Greek mythology, which, in a wholly beneficiant sense, obsessed him. His first novel, about Daedelus and Icarus, The Mazemaker, won the William Heinemann award and his second, the Midas Consequence, about an artist of Picasso's Protean energies were but one side of his writing. In Fabrications he was a fabulist like Borges and in his monograph on Giovanni Pisano, an art historian and scholar. In 1976 he will have a major retrospective at the Birmingham City museum and art gallery.

Guardian 12 March 1982: Exeter, John Dalton

Michael Ayrton

A man in his time plays many parts and Michael Ayrton probably played too many for his own good as an artist. He started his career in 1941 as a theatre designer and although he was variously craftsman and book illustrator, painter and sculptor as well as a TV personality, I feel he was better with words than he was with images and objects. He was a brilliant conversationalist, so steeped in art history, so knowledgeable and acutely critical and aware of facts, that his intuitive gifts and imagination as an artist got buried.

Any show of Ayrton's work looks terribly mannered and eclectic. There are whiffs of archaic Greek sculpture, Renaissance painters like Signorelli, pretty obvious borrowings from Blake and Palmer. Yet he is closest of all to Fuseli (dark dramatic wash drawings, sinister subject matter hinting at corruption and nightmare); his Minotaur etchings of 1971 leaning heavily on Picasso; and, among his sculpture, surely there are references in his head of the brooding Berlioz to Guardier-Brzeska, in his acrobats to Reg Butler, in other aggressive pieces to Germaine Richier and Elizabeth Frink, even in heads within heads to the helmets of Henry Moore? This large exhibition reveals him as a tortured soul expressing himself powerfully. Ayrton's work may be seen in most city art galleries here and America yet seeing so many works -- 177 in all -- one realises how haunted he was by Greek myths and dark gods, and how his work seems locked in the past. There is terror and pathos here but little celebration and praise.

Michael Ayrton: Recurring Themes and Images. Exeter Museum until April 3.

Armand Erpf's Maze

From 'Christmas Greetings 2004', a christmas letter from Robert McArthur of Stevenage, whose wife Ibby was the daughter of Dodo, Cecil Gould's sister.

"In September 1967, Armand Erpf, an American millionaire and a financial genius of Czechoslovak origin who had made a fortune on the New York Stock Exchange, met an English scuptor, Michael Ayrton, at a party in New York. Michael already had a considerable reputation as a stage designer, artist and sculptor and had recently completed a novel "The Maze Maker" based on the life of Daedalus. Michael later said "Armand Erpf was a courteous and well spoken elderly gentleman...... I thought 'This man is mad... what does he want?'" He wanted Michael to build a full-size brick maze in the grounds of his estate in the Catskill Mountains in New York State. Michael prepared some preliminary drawings, despatched them, and thought no more of this strange encounter. Some time later, when Michael was preparing to leave California where he had been lecturing at the university, he received a phone call: "This is Armand Erpf. Go ahead!"

And so on a hot June day in 2004, Jo [Robert's daughter] and I drove some 70 miles north west of her home in New Paltz to Arkville, a small town near to the Erpf Educational Foundation where, some time previously, Jo had given a geographical presentation not knowing that, nearby, was the astounding creation of Michael Ayrton, who was, in fact, Ibby's nephew and Jo's first coursin, once removed!

As the structure is in the private grounds of the Erpf estate, we were met by the caretaker, who led us by a curcuitous route through the woods to the maze. The starting point is actrually a twelve-foot circular mosaid made of local tiles. From this, a path of polished stones taken from a nearby brook leads to the entrance, passing throgh Greek columns that Armand Erpf had acquired and Michael used to celebrate the entrance to the maze itself. One thousand, six hundred and eighty feet of narrow pathways, between walls of brick and stone eighteen inches thick and eight feet high, the maze contains 210,000 bricks in an area two hundred feet across. The double centre is based on the form of the Cretan two-headed axe. To either side, the central chambers contain magnificent seven-foot-high bronze statues, one of Daedalus, the maze-maker, and the other the Minotaur, a monster, half-bull, half-man that Theseus slew with the help of Ariadne. And so, standing with Jo in the centre of this unque structure, we remembered Michael, with whom Ibby and her brother John played when they were children."

https://www.abebooks.com/signed/Femmes-Hombres-Fifteen-Etchings-Michael-Ayrton/22455673785/bd

this suite of etchings is incompletely accessible through google image search

i would imagine they were too naughty for public exhibition at the time they were published

i think, in a way, they are his triumph ...

are they autobiographical in any way ? who knows ?

ayrton had already illustrated a work on socrates,

i guess he saw connections between himself and socrates, and must have been astonished at verlaine's resemblance to socrates

so, is this verlaine, or socrates, an avatar of ayrton, possibly maybe ?

to me it seems that he could identify with verlaine and with socrates

whatever ...

he has simplified his technique down to the linear minimum

and this shows how deep was his understanding of human form and structure ...

hands and feet, fingers and toes, arms and lags, mouths and fiddly-bits ...

each have a naturalistic articulation and weight and momentum distilled through these lines

i wonder if ayrton was "taking on" picasso's vollard suite ? ... i'd rather own ayrton's

this suite of etchings is incompletely accessible through google image search

i would imagine they were too naughty for public exhibition at the time they were published

i think, in a way, they are his triumph ...

are they autobiographical in any way ? who knows ?

ayrton had already illustrated a work on socrates,

i guess he saw connections between himself and socrates, and must have been astonished at verlaine's resemblance to socrates

so, is this verlaine, or socrates, an avatar of ayrton, possibly maybe ?

to me it seems that he could identify with verlaine and with socrates

whatever ...

he has simplified his technique down to the linear minimum

and this shows how deep was his understanding of human form and structure ...

hands and feet, fingers and toes, arms and lags, mouths and fiddly-bits ...

each have a naturalistic articulation and weight and momentum distilled through these lines

i wonder if ayrton was "taking on" picasso's vollard suite ? ... i'd rather own ayrton's

Wednesday, June 5, 2019

stealing from michelangelo ... i need to borrow the outlines of two figures from the twenty ( well there were twenty to begin with ) "ignudi" painted by Michelangelo on the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel ...

My immediate quandary was whether to allow myself the distraction and delay of understanding the ignudis' context, by reading these wikipedia articles ...

( https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sistine_Chapel_ceiling )

( https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gallery_of_Sistine_Chapel_ceiling )

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Restoration_of_the_Sistine_Chapel_frescoes

... describing the ignudi's conception and creation, and so i'm reading for the first time a translation of some verses Michelangelo composed describing the physical rigours of the work, which took him four years...

- I've grown a goitre by dwelling in this den–

- As cats from stagnant streams in Lombardy,

- Or in what other land they hap to be–

- Which drives the belly close beneath the chin:

- Fixed on my spine: my breast-bone visibly

- Grows like a harp: a rich embroidery

- Bedews my face from brush-drops thick and thin.

- My buttock like a crupper bears my weight;

- My feet unguided wander to and fro;

- By bending it becomes more taut and strait;

- Crosswise I strain me like a Syrian bow:

- Whence false and quaint, I know,

- Must be the fruit of squinting brain and eye;

-

- Come then, Giovanni, try

- To succour my dead pictures and my fame;

- Since foul I fare and painting is my shame.

There were twenty ignudi surrounding five scenes from the Old Testament. I wanted to copy only one figure for each side of my picture, each figure's torso turning inwards. The wikipedia article has an excellent picture gallery showing all of the main figures ... BUT ... not all of their illustrations show the complete uncropped figure, and the ones that would sit on the right and face towards the left seem to be in the minority, as far as ideal choices go.

etc, etc.

so, after the search, the choices for the figure on the left of my composition boil down to these ...

and the figures that could go on the right side are more problematic for me and my project, most being too melodramatically gestural, so i only have these ...

every figure on the ceiling is posturally and anatomically complicated and i really don't have the drawing and painting skills to render them, but i have an idea only tenuously connected to them that i want to bring in to the light, so there is much to ponder, and much work and thinking to be done before i can begin ...

the vatican museum have a wonderful interactive virtual tour of the chapel although the image quality is not of such a high resolution as the individual photographs

... http://www.museivaticani.va/content/museivaticani/en/collezioni/musei/cappella-sistina/tour-virtuale.html

Tuesday, June 4, 2019

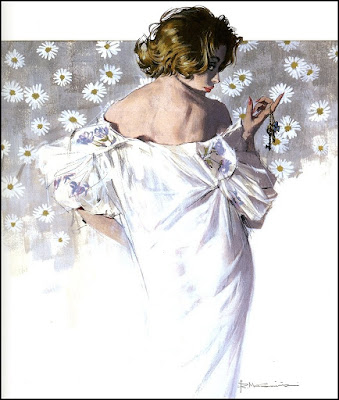

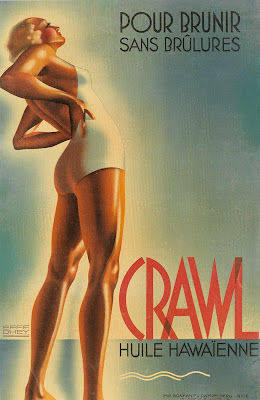

wimmin in white ... part vi ... series v having reached 100 pics, so lets start anew ...

following on from, in reverse order ...

wimmin in white part v ... 100 images ...

http://thenewemotionalblackmailershandbook.blogspot.com/2019/04/#1623861654227863124

wimmin in white part iv ... 200 images ...

https://thenewemotionalblackmailershandbook.blogspot.com/search?updated-max=2018-12-24T05:57:00-08:00

wimmin in white part iii ... 364 images ...

http://thenewemotionalblackmailershandbook.blogspot.com/2018/07/#1351848707561539563

wimmin in white part ii ... 625 images ...

https://thenewemotionalblackmailershandbook.blogspot.com/2015/11/#668097020601761109

wimmin in white ... 500 images ...

https://thenewemotionalblackmailershandbook.blogspot.com/2014/06/#7651911018587671396

https://www.facebook.com/flashbak/videos/563119437553323/?t=13

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)